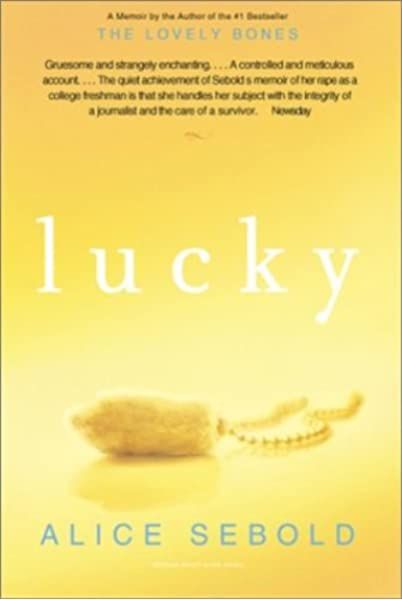

In the book, Sebold writes about how months after the attack, she was walking down the street and saw a Black man that she felt was her rapist. In the book, she writes about the encounter: “’Hey girl,” he said. ‘Don’t I know you from somewhere?’” She was sure it was him. Sebold went to the police but didn’t know the man’s name. One of the officers mentioned Broadwater had been in the area. After his arrest, Sebold was not able to pick him out of a lineup and instead identified someone else. Despite that, Broadwater was tried and convicted on two pieces of evidence: Sebold’s testimony, and expert testimony about microscopic hair analysis tying him to the rape. The latter has been called “junk science” by the US Department of Justice. Scientific advances have weakened the significance and use of hair analysis, particularly before the early 1990s. “Sprinkle some junk science onto a faulty identification and it’s the perfect recipe for a wrongful conviction,” Broadwater’s attorney, David Hammond, told the Post-Standard. After his release in 1999, Broadwater stayed on New York’s sex offender registry, and he worked as a trash collector and handyman. He told the AP that the conviction hampered his job opportunities and impaired his relationships with family and friends. When he got married, he even chose not to have children because he felt so stigmatized. After the conviction was overturned, Broadwater sobbed with relief, overcome with emotion. He told the AP, “I’ve been crying tears of joy and relief the last couple of days. I’m so elated, the cold can’t even keep me cold.” Sebold has also written the novels The Lovely Bones and The Almost Moon. The Lovely Bones, which is about the rape and murder of a teenage girl, was made into a movie. Lucky was in the process of being filmed and is the reason that Broadwater’s conviction was overturned. Tim Mucciante, the executive producer of the film, became skeptical of Broadwater’s guilt because the first draft of the script was so different than the novel. He was trying to figure out why and started exploring. After he dropped out of the project, he hired a private investigator, who put him in touch with Hammond and another defense lawyer. It is not clear what will happen to the film adaptation of Lucky, with Broadwater’s exoneration. In her memoir, Sebold writes, after finding out she picked the wrong man out of the lineup, that the defense would say “A panicked white girl saw a black [sic] man on the street. He spoke familiarly to her and in her mind she connected this to her rape. She was accusing the wrong man.” Sebold has not commented on the case and there has been no response to messages sent to her publisher and literary agency. A Black man serving time for sexual assault is 3.5 times more likely to be innocent than a white sexual assault convict. A major cause of this is misidentification of Black defendants by white victims. In half of all sexual assault exonerations due to mistaken identification, the defendant is Black and the victim is white; this happens in about 11 percent of all sexual assaults in the US. Black individuals are also seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than white individuals. If you are a survivor and need support, RAINN is a nationwide resource. They can also be reached 24/7 at 800-656-HOPE.