The establishment of the Comics Code Authority in 1954 was largely a reactionary measure driven by overall fear of censorship. This was not a great time in history for media in America that was thought to be “dangerous” for children or anyone else.

Fear for the Children in the 1950s

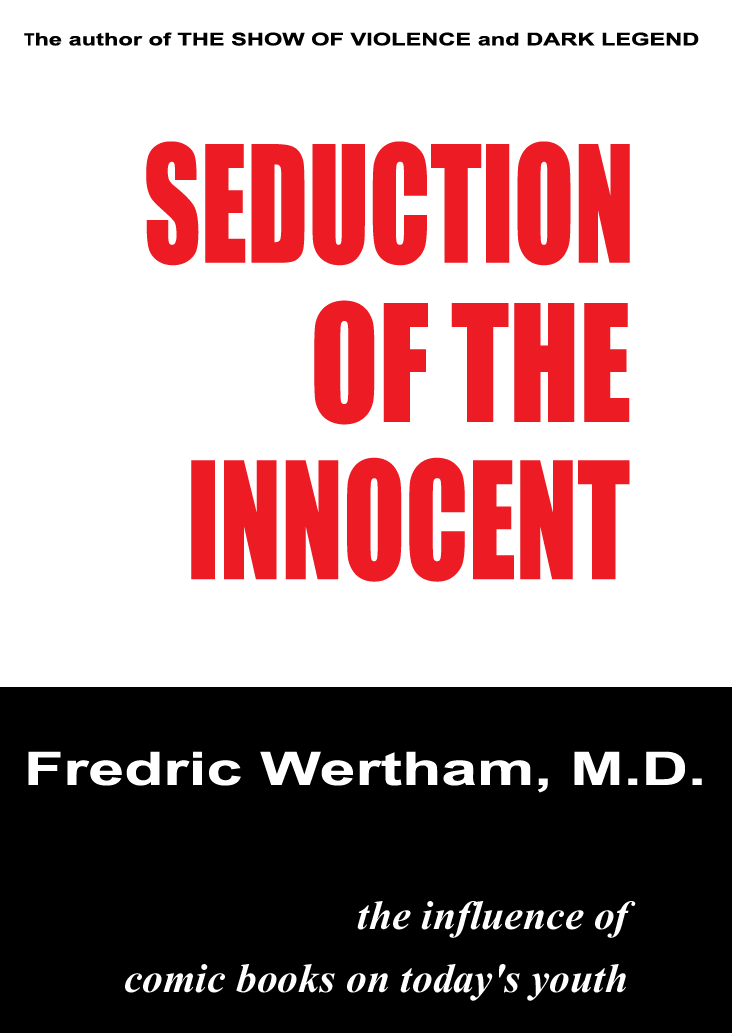

Before the Comics Code Authority, the Motion Picture Production Code (widely called the Hays Code) was applied to most major studio pictures released from 1934 to 1968. It was a self-censorship system to avoid the government censorship that could come down and limit the success of big studio movies. In 1968, this system was replaced with the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) rating system. The reason this worked for as long as it did was because of the studio system. Hollywood was controlled by several large studios that could essentially decide how to make films that made money. For a long time, this meant sticking to the Hays Code. It had many rules that still influence film today: the requirement that queer characters had to be villainous or suffer tragic fates, regulations against the depiction and discussion of adulterous sex, and various other political rules. McCarthyism was also a looming factor in the enforcement of the Hays Code. The House Un-American Activities Committee was investigating a lot of people in the entertainment industry and making random threats based on the fear of people disloyal to American in the post-World War II moment. This general fear of disloyalty made it way down to the five and ten cent comics that kids could pick up at any grocery store. The Comics Code Authority was established in 1954, Dr. Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent accused all comics of promoting delinquency and disregard for authority in children. He made this conclusion by asking young delinquents if they read comics, to which they responded yes. At the time, comics were so common and widespread for children that this would be like asking a kid in America today if they know what an iPad is. In the academic journal Information & Culture, Carol L. Tilley argued that Wertham had largely fabricated and exaggerated his findings to arrive at a neat conclusion. At the time, there was also a series of Senate hearings on the relation of comics to crime, but they did not arrive at the conclusion that comics caused crime. However, parent protests and the general fearfulness around how media influenced children caused the creation of the self-censorship body the Comics Code Authority.

Rules and Influence of the Comics Code Authority

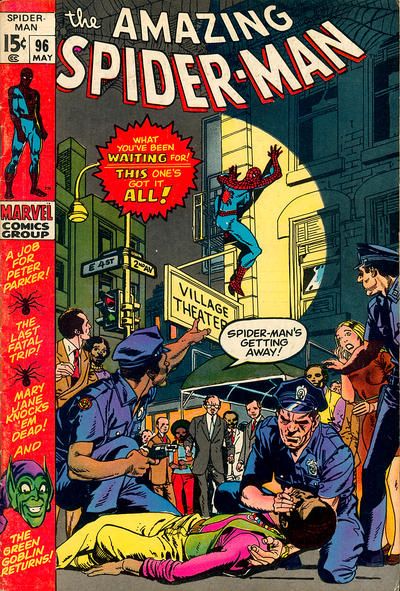

It’s easy to understand how a general worry about loss of revenue through protest would cause voluntary censorship of the comics. They were so widely available that submitting them to the CMAA for a read-over was a small price to pay to get that seal of approval that would allow parents to allow their kids to get comics. If publishers declined to send their comics to the Comics Code Authority for review, their comics could not be stocked in stores. There were 41 provisions to stick to in the Comic Censors’ Bible to get the seal of approval. The general rules that comics had to follow are easy to guess: no sex, no drugs, no cursing, no rock n’ roll, no nudity. The words “terror” and “weird” were banned from comic book titles. Additionally, cops had to always be right and correct, while villains always had to lose. These rules supposedly ensured the avoidance of tainting America’s youth with sex, drugs, villainy, and communism. However, the Comics Code Authority was forced to change and became less relevant over time before the complete abandonment in 2011. In 1971, a review of the code was caused by Marvel’s request to publish special issues of Spider-Man comics, which involved drug use. The Comics Code Authority subsequently relaxed certain rules in a way that was more in line with current freer attitudes towards sex, drug use, and the publication of horror comics with “disturbing” imagery. Similar to the erosion of the Hays Code, the Comics Code Authority just became more limited over time, and people found ways around it. In the 1970s and 1980s, comic book publishers started to find ways to avoid the seal of approval all together. Instead of selling their comic books to stores that required CCA approval, they sold them to comic book shops that served comics lovers of all ages and didn’t necessarily care about parental approval for comics. An example of a movie flouting the Hays Code to great success was Some Like It Hot. It was released without the approval of the Hays Code and was a massive hit. In 1989, the code received updates again, partially because DC wanted to eliminate the seal of approval altogether to give a wider berth to their artists and writers. However, after 1989, the rise of independent comic book publishers and the fact that most comic books could be found in comic book stores meant that they weren’t totally beholden to the Comics Code Authority’s seal of approval. In 2001, Marvel withdrew from the Comics Code Authority’s regulations and designed their own rating system. By 2011, Archie Comics and DC were the last two submitting for seals of approval, and then they were the last dominoes to fall.

Where Are the Queer Superheroes?

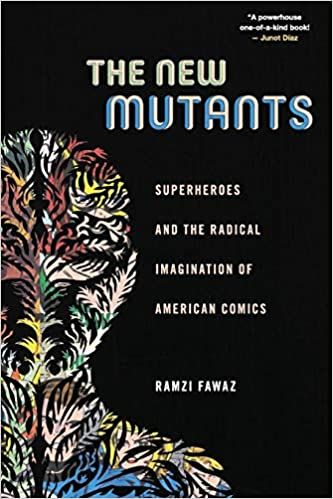

In a similar fashion to comics censorship to meet CCA guidelines, large-scale comic book movies have scenes with queer characters being visibly queer removed from the final cut of the film. This could be a combination of the trickle down of the Hays Code and the Comics Code Authority. A common refrain from the studios is to blame international markets (like China) for the supposed “need” to cut possibly offensive material from movies. The Comics Code Authority definitely regulated what kind of visible queerness was allowed in comics, but many comics historians argue that queerness is foundational to the invention of comics, like Ramzi Fawaz’s comics history book The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics. Video essays by Rowan Ellis and James Somerton also give good historical background to the issues of queer characters, queerbaiting, and queer metaphors in comics.

Comics Regulation Today

Part of the downfall of the Comics Code Authority is probably due to comics readers growing up. Kids who loved comics in the 1950s grew up and naturally wanted to read comics that dealt with more complex, adult themes. Coupled with changing mores around sex, drugs, rock n’ roll, and depictions of violence, the Comics Code Authority quickly became a relic of the past. Comics were thought to be only for kids for a time, and therefore had to promote good, all-American values to the children. However, comics were also an art form with an underground movement and a ton of interest in questioning authority, so it became difficult to maintain a super-wholesome image across all comics media. All publishers have their own internal guidelines and decisions, but the general idea is to tell good stories. Like the rise of independent cinema after the downfall of the studio system, an industry-wide self-censorship body was more difficult to maintain. Nowadays, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund can assist with comics that deal with censorship. It feels more important to protect the right to tell stories than to protect the nebulous idea of childhood innocence. Looking for more facts about the CCA? Check out 10 Things You Might Not Know About the Comics Code Authority.