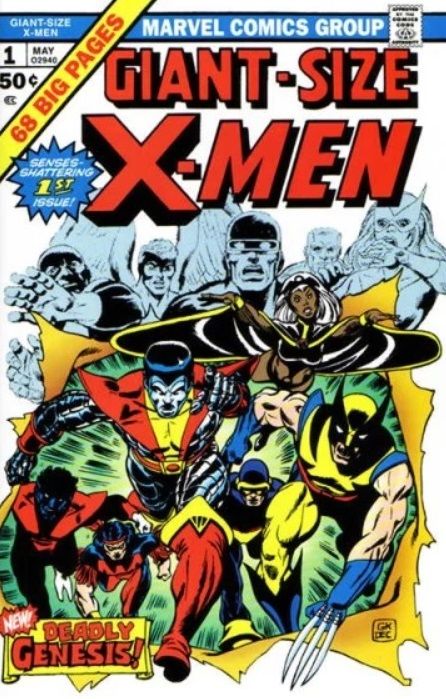

This is hardly the first time comics have mocked a president or, more broadly, gotten political. In their earliest days, they were blatant anti-Nazi propaganda. Although they indulged in anti-communist propaganda in the 1950s, their political ardor was cooled by increased censorship. But by the mid to late ’60s, comic book creators were once again dipping their toes into more contentious territory. They didn’t do it very well, but there was definitely a more sincere (some might say preachy) tone than past attempts at dealing with serious issues. I’ve discussed this topic before, but today I’d like to get a little more in-depth into the Bronze Age, which encompasses comics published roughly between 1970 and 1984. More specifically, I’m limiting this post to comics from 1970 to 1975, with an occasional stop in the late ’60s. This is when Marvel and DC really started to change attitudes in earnest and devote themselves to stories about issues that readers would find relevant, such as…

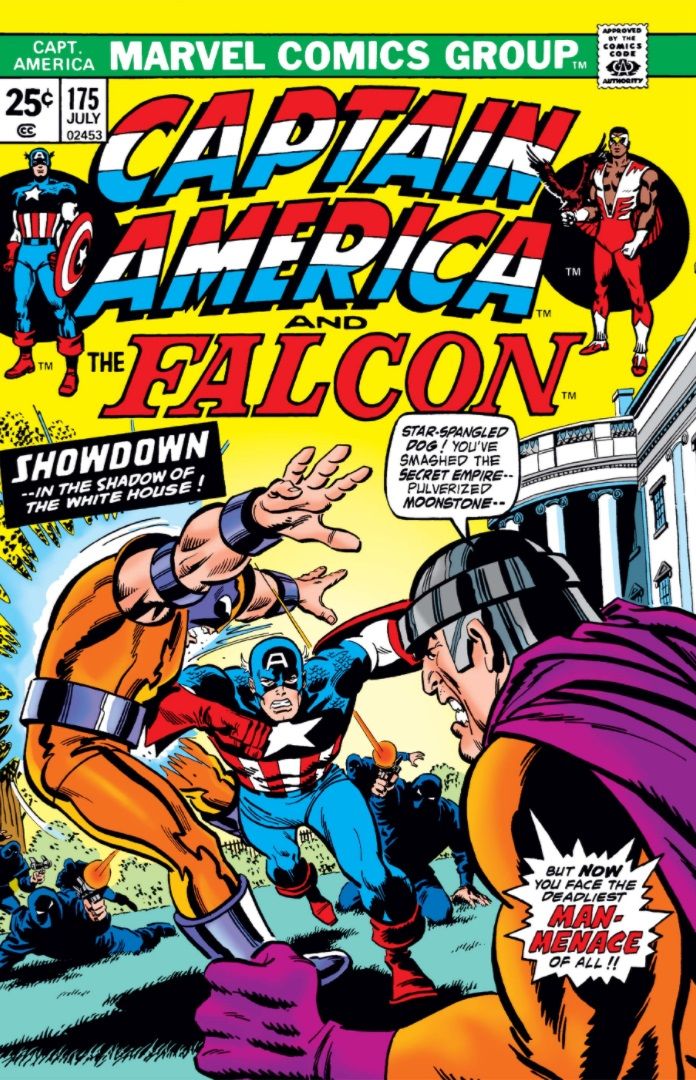

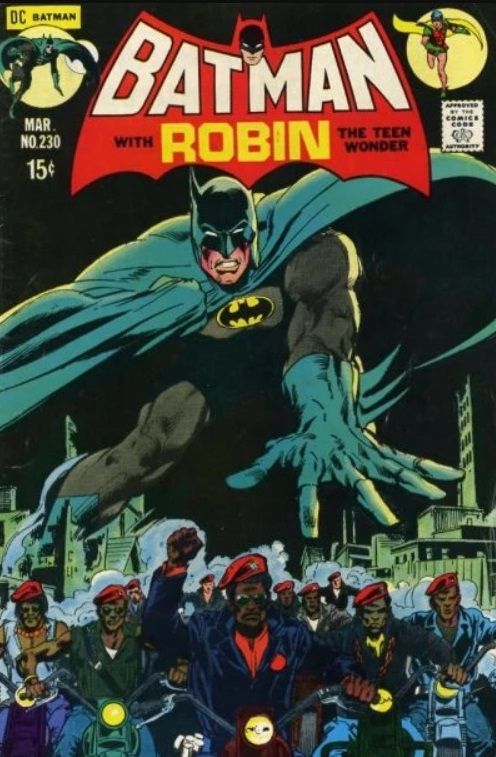

Civil Rights

As today, the ’60s and ’70s were a time of racial unrest in the United States. Comics readers were inundated with headlines about race riots, sit-ins, and the assassination of civil rights leaders. So it was only natural that the (largely non-Black) comics creators would want their (largely non-Black) characters to grapple with the same racial issues their readers were facing. How’d they do? BAD. It is VERY, VERY BAD, why are you even asking?

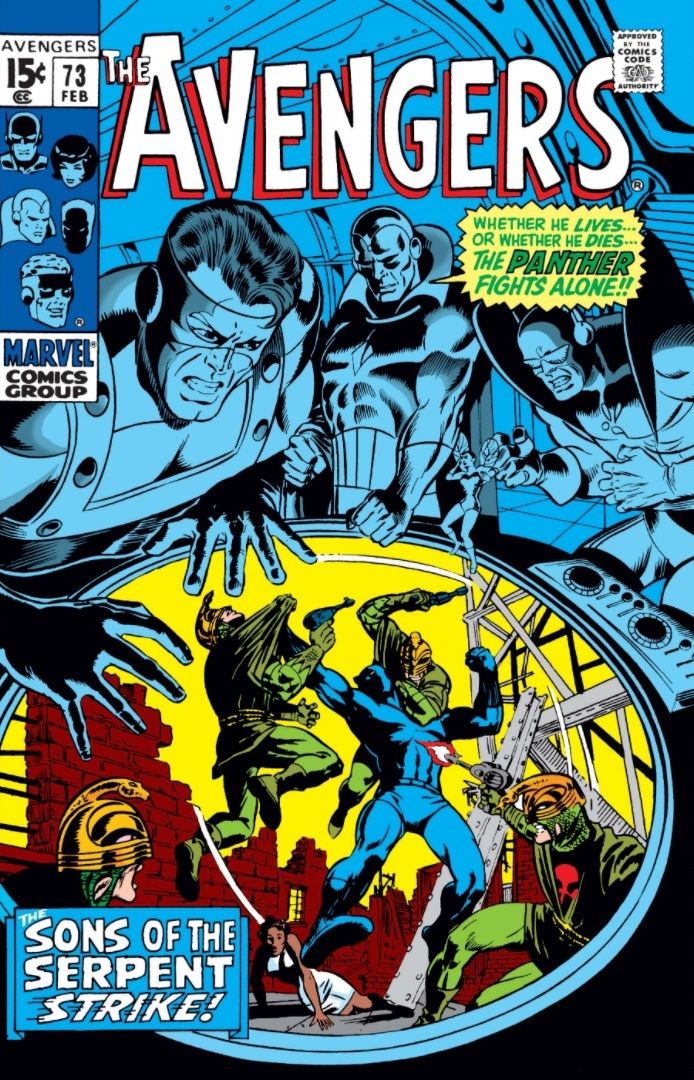

Drugs and “Real” Crime

Sure, comics still dealt with alien invasions, evil mutants, and the like. But starting in the late ’60s, they increasingly dealt with down-to-earth criminals like drug dealers and slumlords. Some even made a career out of it; when he wasn’t the Falcon, Sam Wilson was a Harlem social worker, and Black Panther temporarily gave up ruling Wakanda to become an inner-city schoolteacher. But don’t worry, the Avengers got a rematch against those slimy serpents! And this time, the baddies were led by an actual white American who made a living as a Fox News host by shouting racist trash on TV! Unfortunately, his partner was a Black TV host whose only “crime” up until the big reveal was being angry at the racists who tried to kill him. So…is Marvel’s message that being vocally opposed to racism is equally bad as being a racist? One would hope she’d at least learn a valuable lesson about the challenges Black people face. But no. Instead, a Black guy who was rude to her earlier learns not to be racist against white people. I’m pretty sure that’s the exact opposite of the lesson we’re supposed to be learning, but okay.

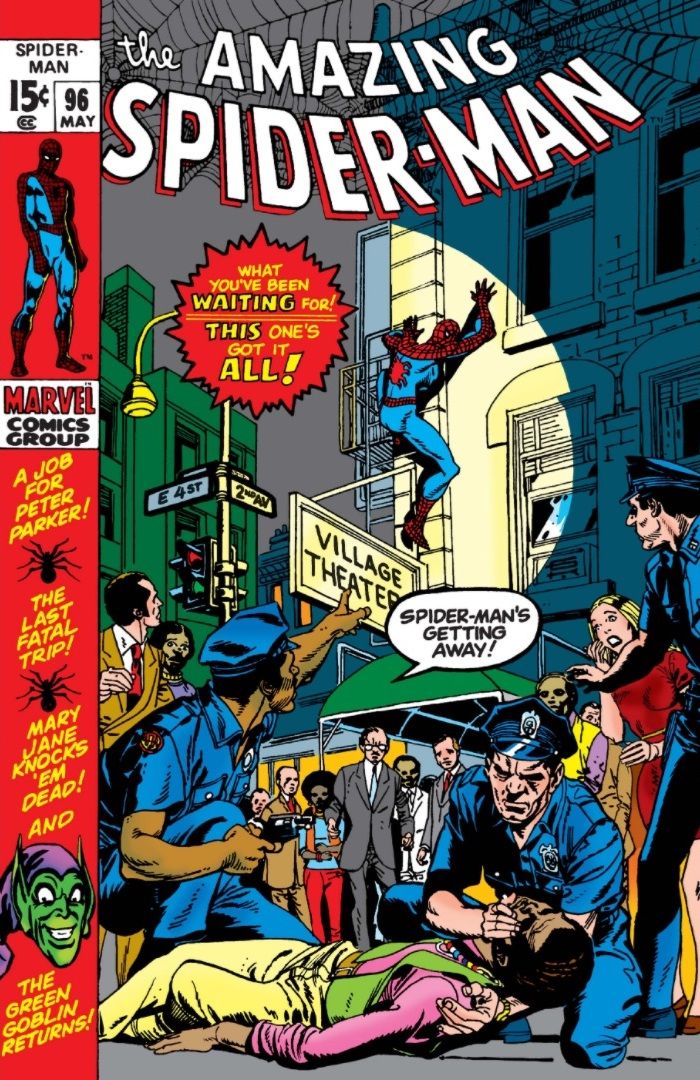

Executive BS

Richard Nixon was president from 1969 to 1974, which nicely coincides with the time period I’m covering in this article. That is not a coincidence. Nixon’s spectacularly unhelpful response to the Vietnam War (more on that later), to say nothing of the way his administration imploded after Watergate, contributed to the disillusionment and discontent that fueled comics creators of the era. This point is reinforced by the next issue. Peter’s white friend, Harry Osborn, has been taking pills to cope with life. Things get worse when he overdoses on a new, unspecified kind of pill and ends up in the hospital. Peter doesn’t say anything to his face about it, but his inner monologue is real condescending. He says twice that Harry is “weak” for resorting to drugs. By contrast, he has nothing but sympathy for Harry’s dad, whose mental problems cause him to become a bomb-wielding supervillain.

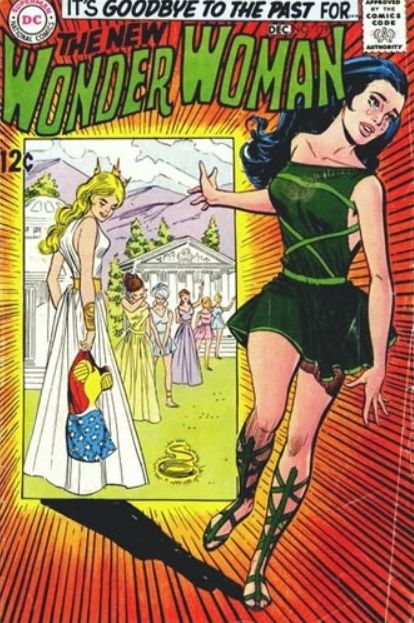

Feminism

Apparently, getting the right to vote wasn’t enough for women, because they kept agitating for things like “fair wages” and “respect.” At least, I assume that was most creators’ attitude towards feminism, because that’s sure what comes across in their comics on the subject. Rattled, Cap spends the next few issues reassessing everything he thought he knew about America and himself. “Like millions of other Americans … he has seen his trust mocked,” and he decides that he just can’t be a symbol of a fractured nation and a self-serving government any longer. Instead, he becomes Nomad, the Man Without a Country (but With Great Cleavage).

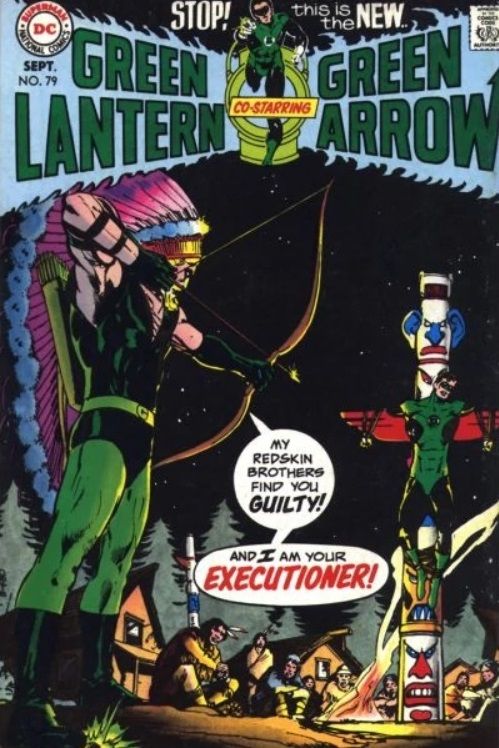

Indigenous Rights

Up until now, Native Americans had largely appeared as stereotypes and joke characters in stories with titles like “Superman, Indian Chief!” (That very story, which appeared in 1950’s Action Comics #148, has Superman time travel to cheat the Native Americans out of the land Metropolis sits on, all to ensure their dickish descendant doesn’t get to own the city. Jeez, Supes.) The Bronze Age saw a series of more sincere attempts at dealing with Indigenous land rights…comparatively speaking. To be fair, Wonder Woman #203 dealt with feminist issues more directly. Wondy went toe to toe with an unscrupulous department store owner who underpaid his female laborers. She got the store to close, at which point the exploited laborers turned on her for shutting down their only source of income. In the next issue, Wonder Woman regained her powers and went back to fighting gods and nonsense. That’s enough serious talk for one decade!

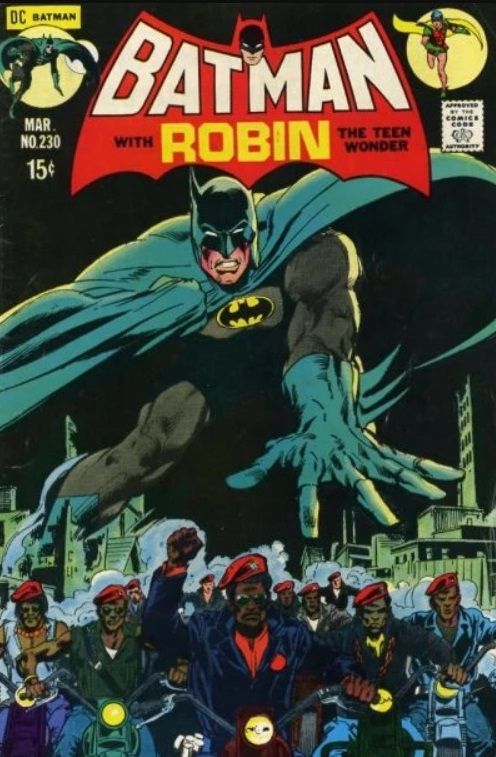

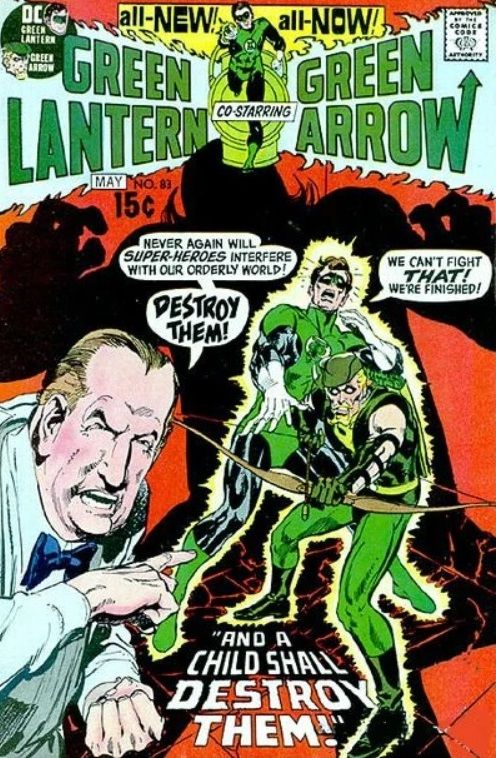

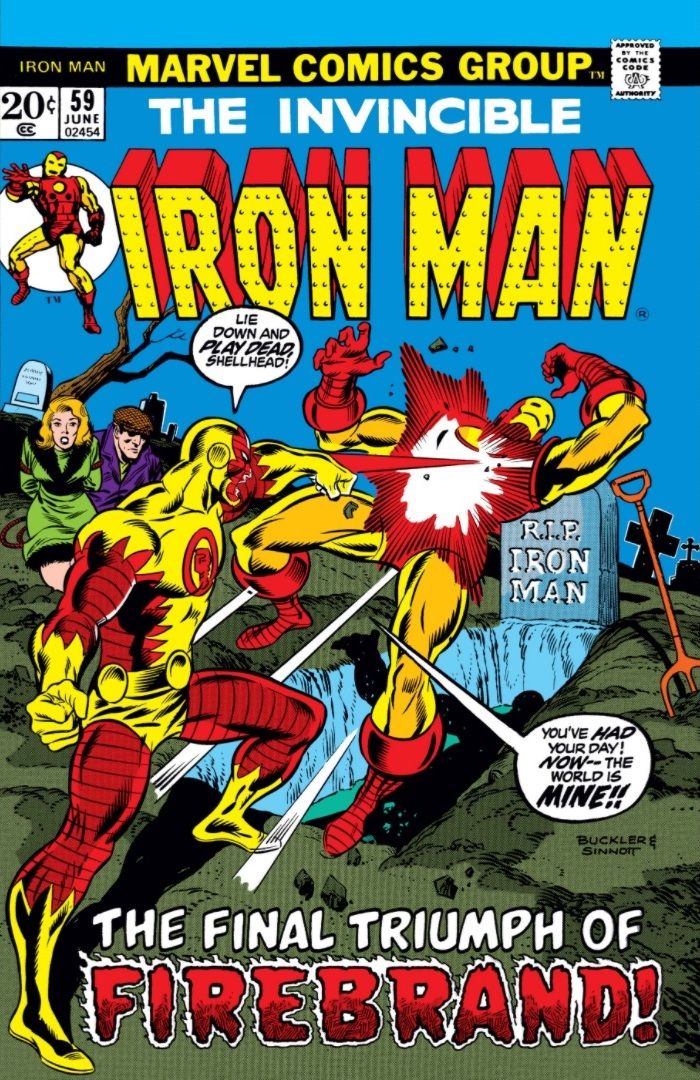

The Vietnam War

America was involved in the Vietnam War for almost 20 years, starting in 1955. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that young people, sick of being drafted into a war they disagreed with, began protesting in earnest. And comic books protested right alongside them. Some heroes, like Daredevil and Captain America, befriended disabled Vietnam vets. Others, especially younger ones like Robin and Spider-Man, got more directly involved…though not in ways you may expect. Like I said, Bronze Age comics didn’t do a great job of dealing with timely issues. You can tell the creators were trying to make meaningful stories, but they generally fell short. Why? In his book Comic Book Nation, Bradford W. Wright states that Marvel in particular received blowback for their increasingly liberal tone. This suggests the creators were caught between two ideologies. On the one hand, they wanted to appeal to hip, modern youth. On the other, they were alienating conservative readers. That could explain the indecisive “very bad people on both sides” conclusions drawn by many of these comics. Firebrand meets defeat thanks to his pacifist sister, Roxanne Gilbert. But when Tony tries to pay her a visit, he is rebuffed; Roxanne is repulsed by the “Asian blood” on his hands, and by all the money he made selling weapons for use in Vietnam. Tony had, in fact, gotten out of the munitions business back in Iron Man #50. In Issue 78, we find out why. While in Vietnam to test a new weapon, he saw a bunch of American soldiers and an entire Vietnamese village die horribly because of said weapon. Iron Man screams melodramatically for a bit before vowing to turn away from weapons and uncritical patriotism. Instead, he will focus on finding peaceful solutions to the world’s problems. Then again, reader support far outweighed reader criticism. So why wouldn’t the creators go all the way and, say, condemn racists in general rather than pinning the blame on a very few individuals, or claiming that Black people were just as bad? Even DC’s cheesy ’50s PSAs managed that much. Was there something else going on? I suggest the following: the creative teams on every single one of these comics were overwhelmingly white and male. Lack of diversity leads to lack of perspective. These creators may sympathize with liberal causes, but they do not have personal experience with them. To this lack we can attribute the less sensitive portrayals and comments, as well as the comic industry’s lingering discomfort with loud expressions of discontent against the establishment: the creators, in many ways, were the establishment. I’m sure that if any of them were confronted with this theory, they would deny it. They would likely be uncomfortable with—even protest—the notion that they, too, were racist and sexist, and that they themselves were what civil and Indigenous rights activists and feminists fought against. But the evidence is right there on the page. We see them compensate for their feelings of discomfort by degrading independent female characters, and urging civility and moderation even in the face of life-threatening oppression. We see how their privilege allowed them to believe that both sides really were equal threats, and that problems like racism really can be traced back to a handful of troublemakers. From that view, “extremists” like vocal protesters probably did look unreasonable, even villainous. For all their faults, these comics represent a turning point in comics history. They signaled that superheroes were once again willing to confront the day’s most pressing issues. It’s a shame they were not up to the challenge.