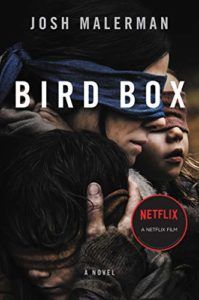

It started innocently enough. I was most of the way through a Harry Potter reread (my go-to reading slump cure) when I decided to take a break between books five and six of that series to read Bird Box by Josh Malerman. (For the record, switching from reading Harry Potter to reading Bird Box is like switching from eating Skittles to eating a habanero pepper.) You might recognize Bird Box‘s title from Netflix’s recent adaptation starring Sandra Bullock, or perhaps from strangers on the internet doing something stupid. See, I wanted to watch the much-talked-about film version of Bird Box but only after reading the book. I started reading late one Sunday morning, and several hours later, I lay in bed wondering if my eyes were burning because I was tired or because I hadn’t closed them more than twice since I started reading the book. As I had blazed through this dystopian fever dream of a book, there was a war going on inside my head. The book’s compelling-yet-grisly concept (humanity is nearly wiped out after mysterious creatures appear and cause anyone who sees them to become violent and ultimately take their own life) was fighting it out against my powerful aversion to anything where children come to harm or are even put into harrowing situations. This aversion struck me, as I’m sure it does many people, after I became a parent nine years ago. Prior to that, I’d had a pretty high tolerance for books and films depicting awful things happening to people. And I honestly believed that I would be able to maintain the ability (if that’s what it was) to compartmentalize my real life experience as the caretaker of a newborn from my book and film intake. So foolish, and so, so wrong. I had, for example, read and loved Cormac McCarthy’s The Road a few years before my son was born. I pressed this book into people’s hands, you understand. I stumped for it. In that novel, a father and his young son navigate a hellish post-apocalyptic version of the southern U.S. in hopes of finding civilization and, with it, safety from murderous bands of lawless thugs. A film adaptation was announced, and I rejoiced. But, by the time the film had been released, I had become a father. The night my wife and I went to see the movie, we left my five-month-old son with my mom. He was supposed to spend the night, but after white-knuckling my way through the movie, there was no way I could have spent the night away from him. It was nearly midnight when we left the theater, but still we went and retrieved him. I needed him near me, as though the constant peril facing the characters in The Road was beating down my door. I am no less affected by these kinds of stories today than I was in 2009. I can’t divorce the terrible things happening on the page or screen from my own anxieties about parenthood. Naturally, this might lead you to wonder why, then, I thought it was a good idea to read Bird Box. I mean, the book’s movie tie-in cover depicts a blindfolded Sandra Bullock and two blindfolded children, their dirty, cut faces pressed close to hers. It might as well be a big red STOP sign. I can’t answer the question. Maybe it was just the cultural pressure of seeing and hearing so much discussion about the adaptation. Maybe I was subconsciously ready to see if my old callouses had re-formed. Whatever the reason, I dove right in, taking periodic breaks to free myself from the book’s considerable narrative tension. By the time I finished Bird Box that night, I had pretty thoroughly tested my readerly limits. I made it through, however, and along the way I think I came to better understand what it was about books like The Road and Bird Box that fundamentally changed what I could and couldn’t tolerate when it came to stories about kids and all the things we parents fear might happen to ours. Because that, for me, is the bottom line. Parenthood is terrifying, and though I (thankfully) do not have to raise my children while contending with the post-apocalyptic nightmares facing the father in The Road or Malorie in Bird Box, I find myself asking the same kinds of questions that fill the minds of both of those characters. Is this the right choice? How do I protect my kids without keeping them from finding their own ways in the world? How much can I teach them, and how much do they have to discover on their own? The questions, the doubts, the fears, they never end. Not for me, and certainly not for the parents at the forefront of these novels. It seems important that in neither work do we get an explanation of why these parents find themselves in these brutal new worlds. The disaster that fills the sky with ash in The Road is never explicitly mentioned. In Bird Box, the origin of the madness-inducing creatures is a mystery. In these novels, why is a secondary concern. All that matters to the protagonists is keeping alive the hope that they might give their children a chance at life. And sure, in both books, the worlds into which these parents are thrust unwillingly are dangerous in truly horrific ways. Their fears seem more immediate than mine, perhaps. But have you looked around recently? The actual world is also a dangerous and sometimes horrific place. And so, in a very weird way, Bird Box actually made me feel better about parenthood, not worse. No, it didn’t assuage my fears or provide answers to that endless list of questions. But it made clear that parents everywhere, in every situation, face their own uncertainties. And not to get all English teacher-y on you, but the fact that Bird Box‘s protagonist does much of her parenting blindfolded makes it clear that its author understands something fundamental about how it sometimes feels to look at your kids, then look at the world around them, and wonder how you’re going to help them get where they’re going. It’s good to know I’m not the only one.