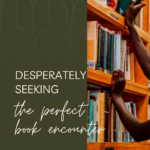

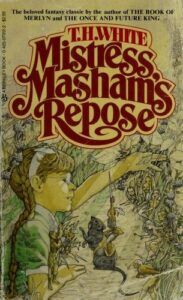

Also, we had watched The Neverending Story possibly over a dozen times by this point in our young lives. The nostalgic classic fantasy film, based on the children’s book of the same name by German author Michael Ende, translated by Ralph Manheim, had long ago shaped my vision of the perfect book encounter. I’m certain I’m not alone in deeply relating to bookish Bastian, who turned to immersive stories for an escape from a lackluster and stressful reality. While we didn’t all get chased by bullies before being unceremoniously tossed into a city garbage bin (what horrors did Bastian face there?), a kid’s life is rarely the wonder-filled burden-free zone of joy we sometimes filter it into. Where Bastian was a skinny white boy grieving his mom and fleeing bullies, I was a biracial Black and Asian kid people liked to call “chubby” and who had difficulty verbalizing beyond the safe circle of my immediate family and close friends. Because speech didn’t come to me easily, because I wanted to be outside of a body I then considered ugly, and because I never seemed to fit in anywhere or to be wanted, reading and writing increasingly became my safe spaces. And so the bookstore became a portal to the multiverse, promising endless opportunity for the kind of escape that would allow me to forget myself; only by forgetting myself could I be comfortable in my own skin. As in other bookstores, I experienced a certain weightlessness entering that musty, dusty bookstore in Old Pasadena. My memory has turned the store’s only employee, likely its owner, into Bastian’s bookseller, even though it’s unlikely they bore any resemblance beyond a sort of mischievous professorial look. He hardly acknowledged our existence. Even better. I felt free to explore to my heart’s content. I instinctively sought out fantasy — I had a talent for finding this section quickly no matter a bookstore’s lack of organization. I was in search of The Book. Bastian had discovered The Neverending Story in a similarly musty, dusty bookstore. This was the moment I’d been waiting for because, like Bastian, I wanted to be special and didn’t believe myself capable of specialness. I’d been taught in so many ways — by media, by peers, by teachers, friends, and, yes, even by my own precious books — that specialness and even the potential for specialness belonged to certain types of people. I was reminded of this when my third grade class made fun of the “gross” soy milk I’d brought in my lunch (I squeezed it onto the concrete to prove I didn’t like it either and cried about it later), when my babysitter gave me SlimFast, when I overheard a girl in my class say she didn’t feel comfortable going to school with Black kids, and on so many other occasions. I wasn’t white or slender or in possession of a certain type of confidence. Perhaps I could’ve taken solace in the rare character described as having “dusky” skin and coming from an “exotic” culture. I did pay extra attention to these characters in books by white authors and sometimes felt a desperate pressure to celebrate them. But the ways in which they were handled often left me uneasy, and in the end they had nothing to do with me. My culture — the Singaporean and Muslim traditions that dominated my and my sister’s upbringing in our matriarchal household, with bits and bobs of African American culture from my father — has historically been deemed not exotic but inscrutable and unrelatable. Anyway, if you were a dark-skinned protagonist in those fantasy novels you had to be gorgeous and fierce or GTFO. So I sought out characters like Bastian who struggled with confidence or were bookish and not considered attractive by their peers. The shy, nerdy character was always white, but the personality was the point of relatability I could occasionally find in the fantasy books available to me back then. Maybe, I theorized, if overlooked underdog Bastian could find The Book and unlock the secret to specialness, so could I. I just had to find the right bookstore. I had a thing for mass market paperbacks because I could fit many of them into my backpack, and my now dusty finger traced the spine of a book with a fun title: Mistress Masham’s Repose by T.H. White. The book opened to a Fritz Eichenberg illustration depicting a bespectacled, cross-looking girl in a dress that had an Alice (of Wonderland) appeal. She frowned out of the page and was flanked by a severe woman wielding a ruler and a severe vicar wielding a Bible. “Unfortunately she was an orphan, which made her difficulties more complicated than they were with other people.” I read this sentence on the first page of the book, and thought, Could this be the one? While I enjoyed Maria’s adventures with the Lilliputians in and around the “enormous house in the wilds of Northamptonshire,” and gained a big love for a certain style of irreverent, cerebral humor typical of White and also of future fave Terry Pratchett, it was not The Book. Still, that bookstore endures in my memory because it’s the closest I ever came to the perfect book encounter. As I grew older and more critical of how specialness is bestowed, of how stories are told and whose narrative dominates conversations, and of the publishing industry as a whole, I focused less on finding The Book and more on investing in my own belief in my specialness. I also celebrated pushes for diversity in publishing and books by authors of color, including Black authors and AAPI authors. Like many writers before and after me, I placed more importance on writing when I first read Toni Morrison’s quote: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Maybe, I theorized, if I haven’t found The Book, it’s because it’s in me.