“A black tide of perversity, violence, and lush writing. I loved it.” —Joe Hill. Debut author Jennifer Giesbrecht paints a darkly compelling revenge tale in The Monster of Elendhaven, a gothic fantasy about murder, a monster, and a magician who loves both. The city of Elendhaven sulks at the edge of the ocean. Wracked by plague, abandoned, stripped of industry and left to die. But some things don’t die easily. The monsters of Elendhaven will have their revenge, even if they have to burn the world to do it. As far back as I can remember, I’ve craved spooky stories that belong in a crypt. Picture books like Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are urged me to imagine the untamable, ambiguous wild. Illustrators like Quentin Blake and Stephen Gammell brought creepy stories to light—or, rather, resurrected them—in scratchy, surreal images infused with twisted terrors. Ever the goth girl, I memorized Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark and other installments in the series, reading them with a flashlight under a cocoon of blankets.

My Goosebumps books took a beating, their pages warped with swimming pool water, their spines cracked, the titles flaked off beyond recognition. I also loved Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and Edgar Allan Poe’s poems and short stories, which I found on my English teacher father’s sturdy wooden bookshelves. My diet of doom wasn’t limited to books, either. Movies like Poltergeist that aired in the early morning witching hour captivated me, the picture fuzzing in and out of grainy static. Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas was a huge influence on me, along with other spooky kid movies, like Frankenweenie, Hocus Pocus, The Addams Family, and Casper. See, I wanted melancholy. I wanted morbid. I wanted maudlin. Because the truth was, I recognized myself in these stories. I wanted protagonists like me.

Horror Gave Me the Framework to Confront My Demons

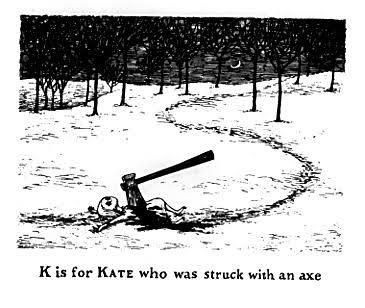

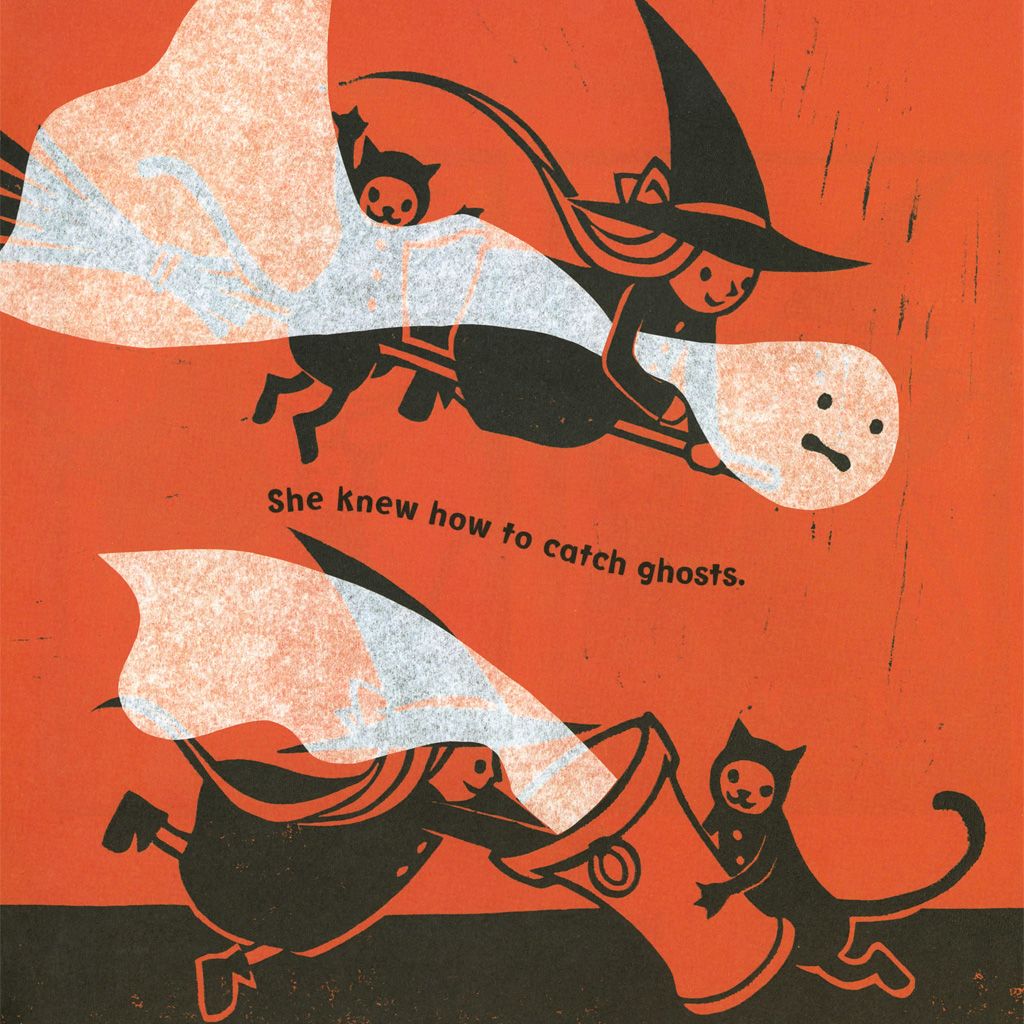

As a child, I confronted evil every day, in the form of sinister people like cruel bullies but also in my troubled mind. I struggled to articulate the complex emotions from depression. I preferred playing alone to joining my peers on the playground; my social anxiety was magnified by undiagnosed Asperger’s. Instead, I developed my own little fantasy role play world featuring my dolls and stuffed animals. Creating and illustrating my earliest stories gave me an outlet for my imagination, a refuge of escapism, and the confidence to start thinking of myself as a protagonist in my personal narrative. Part of the alienation I felt from my peers was my struggle to relate to my carefree classmates’ joy and wonder. But in horror, I found other children who, like me, were dealing with anxiety and melancholy, which made horror stories comfortable, familiar, and even cozy. It’s no surprise, then, that the characters I most identified with were fairytale heroines who battled evil, like “Hansel and Grethel” and “Little Red Riding-Hood,” or certain death, as in “The Little Match Girl.” The stars of Roald Dahl’s grim novels and macabre master Edward Gorey’s quirky books made me feel seen. All along, horror had been priming me. I realized the depression stalking me was just like a shadowy creature lingering in the corner of my eyes. A bully once physically restrained me from sleeping during slumber parties by beating me with pillows. It’s no surprise that I subsequently developed a phobia that a creepy man lived in my closet, ready to come out and steal my soul if I fell asleep. The basis for this creepy closet-dweller might have originated in an Are You Afraid of the Dark? episode, but he became an embodiment of my trauma. Somehow, defeating him every night felt easier, as eventually I’d fall asleep and live to see another day. After all, I had tools for challenging my personal hell; I only had to look in those waterlogged Goosebumps paperbacks to learn that, while scary tales share my menacing fear, they have something crucial: endings. Years later, I’m still confronting the psychic wounds of those younger days. My appreciation for the macabre has only grown, and now I’m writing books and poems of my own about children who dabble in darkness and meet unfortunate ends. What’s changed is how I see horror in children’s literature critically as an essential craft tool for articulating and processing fear.

The Comforting Creepiness of Horror in Kid Lit

I wasn’t the first—or last—child to be saved by storytelling. But now, in the course of my graduate program in writing for children and young adults, I’ve come to appreciate even more how horror is particularly well suited to kid lit. One great example of the effectiveness of horror in kid lit comes from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. A memorable chapter sees Harry Potter and his classmates battling a boggart in a wardrobe. When the door opens, the boggart takes the shape of each student’s deepest fears. Defense Against the Dark Arts Professor Remus Lupin guides them through the frightening experience, teaching them to shout “Ridikkulus!” and diminishing the foe by imagining a silly version instead.

via GIPHY Lupin also helps Harry develop a strong Patronus to banish Dementors, terrifying creatures that initiate depression-like feelings. J.K. Rowling’s book is a master class in how to incorporate scary creatures and encounters that complement internal emotions. And, here’s the part I’m really passionate about. Horror validates fear, rather than dismisses it, and it provides children with a model of how narrative works so they can apply it to their real lives. A scary, supernatural enemy (or some kind of cosmic horror creation) gives children a vocabulary to describe their own fears, depression, and anxieties. Instead of contending with some vague, amorphous feeling that defies expression, kids can point to a metaphorical representation of their inner (and outer) challenges. We often use the phrase “inner demons,” but through horror, kids can point to something that embodies their internal fears. Graphic novels, comics, and illustration enhance horror-based texts even more. True, horror is most frightful when teasing ambiguity; a monster might be under the bed, or it might just be a pile of old shoes. But leaning into that ambiguity is just as helpful, for kids learn that rarely are endings clean cut. Rather, it’s our choice to face our fears, sometimes alone, but often with allies we ask for help, that gives us courage and empowers us to feel in control. Through the art of consuming and creating stories, then, children can learn to fight back, to grasp a lantern in hand and light up the darkness, illuminating the ghost in the corner that, actually, is just an old sheet. Kids can also find the courage to ask for help solving the frightening aspects in their lives. To be clear, horror won’t—and can’t—prevent or banish serious real world dangers that should better be handled by trusted adults and authorities. But I do believe horror in children’s literature can empower alienated kids to identify with protagonists facing fear, recognize invisible torments like psychological distress, and comfort themselves with narratives where the darkness can be overcome. I’ll always be a goth girl at heart. Give me a creepy story any day. Or watch me—I might just craft one of my own. I’ll erase the man in my closet by turning on the light, throwing open the door, and confronting him straight on, fearless.