Or maybe it’s propaganda. That’s what it’s called when the government tries to influence the way we think, isn’t it? What’s the difference between PSAs and propaganda, anyway? As you’re reading this, you will probably have some pretty strong opinions about whether to classify a given example as one or the other. But this is something of a trick question as they are often the same thing. The prologue of Wendy Melillo’s How McGruff and the Crying Indian Changed America: A History of Iconic Ad Council Campaigns defines a PSA as a campaign that “use[s] commercial advertising methods to frame issues with the intention of altering public opinion, changing behavior, and motivating citizen involvement in beneficial causes” for the purpose of “solv[ing] social problems.” Meanwhile, Merriam-Webster defines propaganda as “the spreading of ideas, information, or rumor for the purpose of helping or injuring an institution, a cause, or a person.” There’s a lot of room for overlap there, to be sure. The term “propaganda” has negative connotations, but it is not inherently bad or good. It has certainly been used for bad or questionable purposes — Melillo’s book acknowledges that the Ad Council’s creation was also a ploy to get the federal government to back off proposed regulation of the advertising industry — but you can say that about a lot of things. Regardless of their true definitions, whether we refer to something as propaganda or a PSA is largely a matter of personal values. If we like what we see, it’s a PSA; if we don’t, it’s nasty, dirty propaganda. I’ll be using the terms more or less interchangeably for expediency, not because I’m making a value judgment on any of the material here. Trust me, if I have something bad to say about any of these ads, I’ll come right out and say it. As you can imagine from these definitions, PSAs/propaganda can cover just about any topic that is linked (legitimately or otherwise) to the public good, from bullying to bigotry, from drug abuse to sexual abuse, from wearing seat belts to performing self-exams. We’ll be looking at all of these topics here, so if any of them might be a trigger for you, please proceed with caution (or not at all — mental health first!).

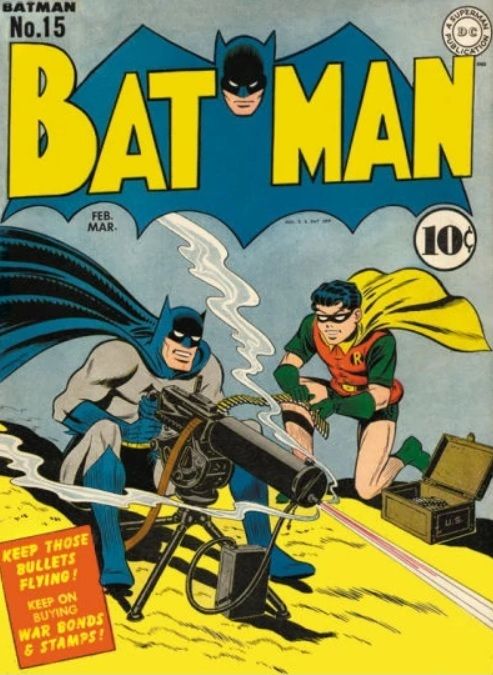

“Keep Those Bullets Flying!”

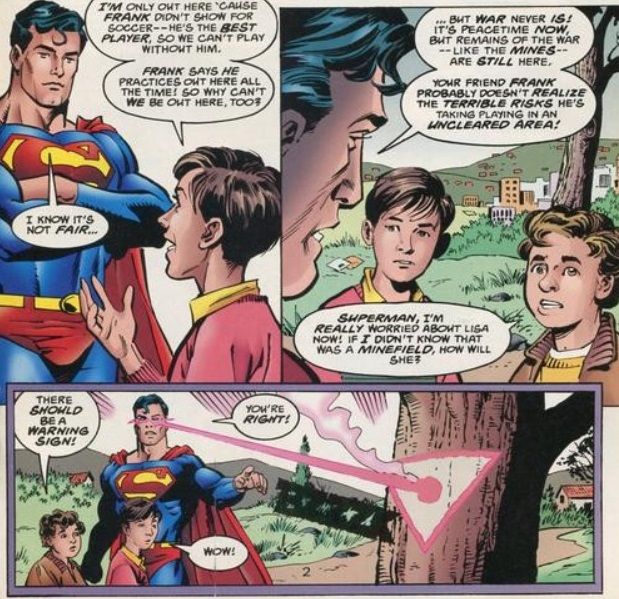

America’s entry into World War II sparked what is probably the greatest flood of PSAs (including the creation of the Ad Council) in the country’s history. This neatly coincided with the creation and popularization of superheroes, who happily did their part to promote the war effort. Sometimes, these PSAs took the form of simple messages tacked onto a cover, in a one-page ad, or at the end of the story. On the cover above, you can see a text box in the corner that urges readers to “keep those bullets flying! Keep on buying war bonds & stamps!” Very often, propaganda was baked into the story, like this one about Batman and Robin touring America to convince people to buy war bonds. And a lot of times you’d get both. Pro-war, anti-Axis propaganda was so pervasive that comic books themselves seemed to become one big PSA. There was even a sub-genre of patriotic heroes created for the express purpose of encouraging reader support for and involvement in the war effort. Most of these characters didn’t have enough substance to survive the war’s end, with the most notable exception being Captain America. Given the virulent anti-Japanese racism that accompanied pro-war sentiments, it’s inevitable that many of these messages have not aged well. Heroes use racial slurs without a second thought, and the Japanese characters themselves are often drawn as horrid, inhuman caricatures that can only be vanquished if you buy bonds or save paper, or whatever the message du jour is. While superheroes no longer encourage armed conflict, war-inspired PSAs do still crop up from time to time, including this 1996 story, Superman: Deadly Legacy, about landmines left behind from the Bosnian War. As the The New York Times reported at the time, the comic was published in several languages and distributed in affected areas.

“It’s No Joke — It’s the Federal Equal Pay Law!”

Superhero PSAs are usually published in conjunction with some other organization that sees value in the heroes’ popularity and figures that the target audience would respond well to messages delivered by those heroes. Deadly Legacy, for instance, was done in partnership with UNICEF and the U.S. government. In the ’40s and ’50s, DC regularly teamed up with organizations like the National Social Welfare Assembly (now the National Human Services Assembly) or the National Conference of Christians and Jews (now the National Conference for Community and Justice). The resulting one-page PSAs featured Superboy, Superman, or Batman encouraging readers to be open-minded and refrain from judging others based on skin color, religion, or whether or not their mother makes Swedish meatballs. These ads discussed equality in terms of race, nationality, and religion. Promoting gender equality seems to be rarer. One example is this TV spot from the early ’70s, in which Batgirl delays saving Batman and Robin from a bomb to complain about how Batman pays her less than he pays Robin. This raises a whole host of upsetting questions, though its primary purpose is to raise awareness for the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Please ignore the title of this video — that is not Adam West, it’s Dick Gautier. (They did get Yvonne Craig, Burt Ward, and narrator William Dozier, though.) West delivered plenty of his own mini PSAs throughout his time on the ’60s Batman show, mostly by reminding Robin to not throw dangerous stuff into the street or to keep his seat belt buckled. (Almost no one wore seat belts at the time. Batman notwithstanding, that didn’t change until states passed mandatory seat belt laws starting in the 1980s. And yes, “freedom lovers” were just as pissy about it as they are now about COVID vaccines.)

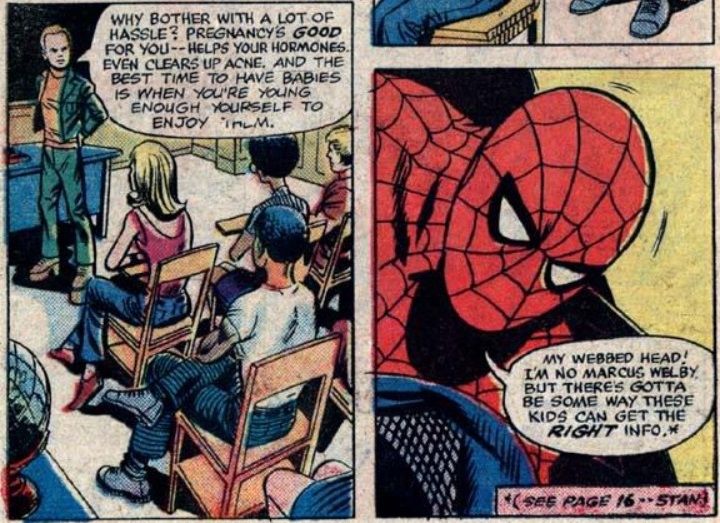

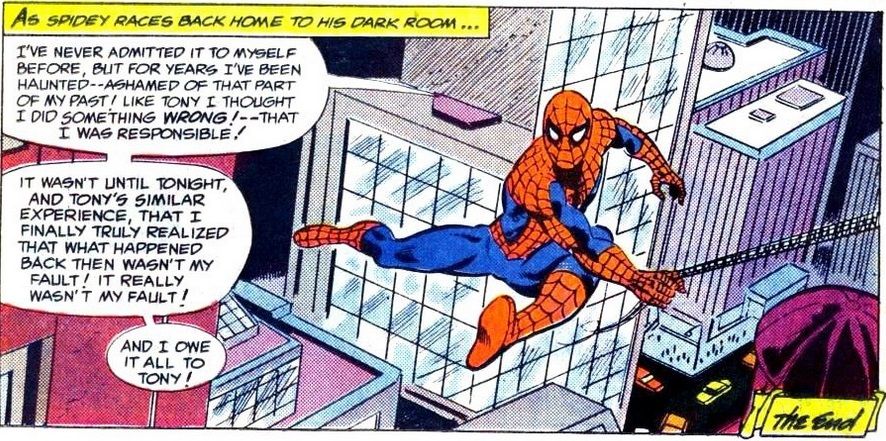

“He Wants Them to Be Baby Machines!”

Since comics were traditionally aimed at a younger audience, it makes sense that a lot of superhero PSAs deal with issues of concern to kids and teens. In 1976, Marvel published a whole comic, Pull of the Prodigy, in conjunction with Planned Parenthood about the importance of sex ed. Well, technically, it’s about an alien trying to brainwash teenagers into having unprotected sex so that he can kidnap all the resulting babies to perform menial labor on his home planet. Why couldn’t he just kidnap children who’d already been born? Because then we wouldn’t have this sweet, sweet PSA, that’s why. On a darker note, in 1984, Spidey also starred in a PSA about preventing child sexual abuse. He helps a kid whose babysitter molested him by relating the story of how he himself was once molested by a kid at school. Like Peter doesn’t have enough problems.

“…And We’ll Beat This Thing Together.”

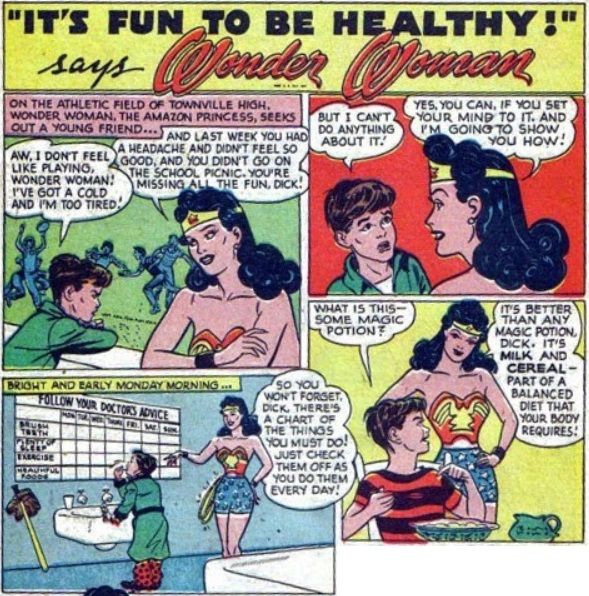

As we have all been forcefully reminded these past couple of years, illnesses, especially new ones, can cause a lot of damage. PSAs are one way to inform the public about the risks of a disease and what they can do to keep themselves and others safe. Aside from COVID, AIDS has probably been the subject of the most lies and misinformation in recent years. In the early 1990s, DC had their heroes dispel the most damaging misconceptions — including the idea that only “bad” or gay people get it — and direct readers to the National AIDS Hotline. (There are actually two versions of this ad. The one above features John Stewart and the alternate features Hal Jordan, but otherwise they’re identical. Not sure what’s up with the copy-paste: there are other ads in this campaign featuring other characters in completely different scenarios, so it just seems lazy.) That said, people sometimes need guidance about more “established” illnesses as well. Hence these 2016 videos in which Deadpool teaches viewers how to do self-exams to check for breast cancer and testicular cancer. Truly the hero we need AND deserve. Finally, there are health-based PSAs that discuss the reader’s general health, like the 2000s “Verb: It’s What You Do” campaign that used the casts of TV’s Teen Titans and Justice League: Unlimited to encourage proper exercise. Then there’s this one, where Wonder Woman has to take over for this unhealthy kid’s hideously negligent parents. This should probably be a PSA about child abuse, actually.

“Be a Hero…Stay Drug Free!”

Anti-drug PSAs are particularly infamous. Despite some evidence suggesting some of these ads worked exactly as intended, they are often criticized for being over-the-top, oversimplified, and just plain ineffective. They did not become any better for adding a few superheroes into the mix. The Health Education Council sponsored a campaign in which Superman went up against the evil Nick O’Teen, a yellow-toothed fiend who was easily defeated by separating him from the cigarettes he depended on. Later, the Teen Titans briefly welcomed a new member, the Protector, to teach kids about drugs. This despite the fact that Speedy the heroin addict is literally standing right there, making the Protector look even more like a superfluous poser. Marvel did quite a few ads about alcohol abuse. The worst (but definitely most hilarious) is probably this one, in which the Punisher threatens to come to your house and shoot you if you drive drunk. The most appropriate one is a far more innocuous ad featuring Iron Man, himself an alcoholic, done in conjunction with the National Association for Children of Alcoholics. But the absolute greatest anti-drug PSA is surely 1990’s Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue, a TV special featuring characters from almost every popular cartoon of the day, from Bugs Bunny to the Muppet Babies. More relevant for our purposes, Michelangelo from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles pops in to remind us that drugs, like, totally mess up your mind, dude. So what have we learned today? With all of this propaganda, surely we must have learned something. I think the main takeaway is just how difficult it is to do a PSA well. When you’ve got only one page or a 30-second commercial to make your point, it’s all too easy to misrepresent the problem or push easy, feel-good solutions that don’t actually work. PSAs delivered over the course of an entire issue or a lengthier YouTube video at least have the time for more nuanced discussions, though that doesn’t help if the creators behind the propaganda allow personal prejudices to derail the campaign. So length in and of itself is not an indicator of quality. Nor is a superhero’s presence a guarantee of success. Batman, despite achieving ungodly levels of popularity in the ’60s, did not inspire nationwide seat belt usage, and one reviewer recalls being so excited to see all of his favorite characters on Cartoon All-Stars that he failed to absorb the anti-drug message. So where does that leave the superhero PSA? We might remember certain ads for being especially egregious or ridiculous, but do we ever take them to heart? Maybe you and I didn’t, but maybe someone out there did, and maybe it made a difference in their lives. And maybe that’s enough.