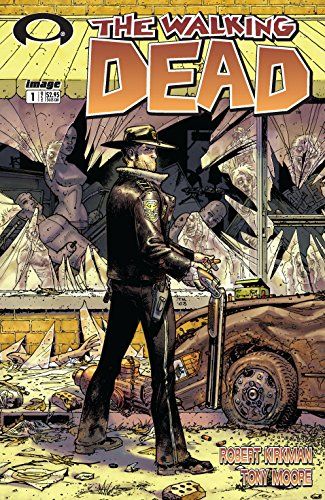

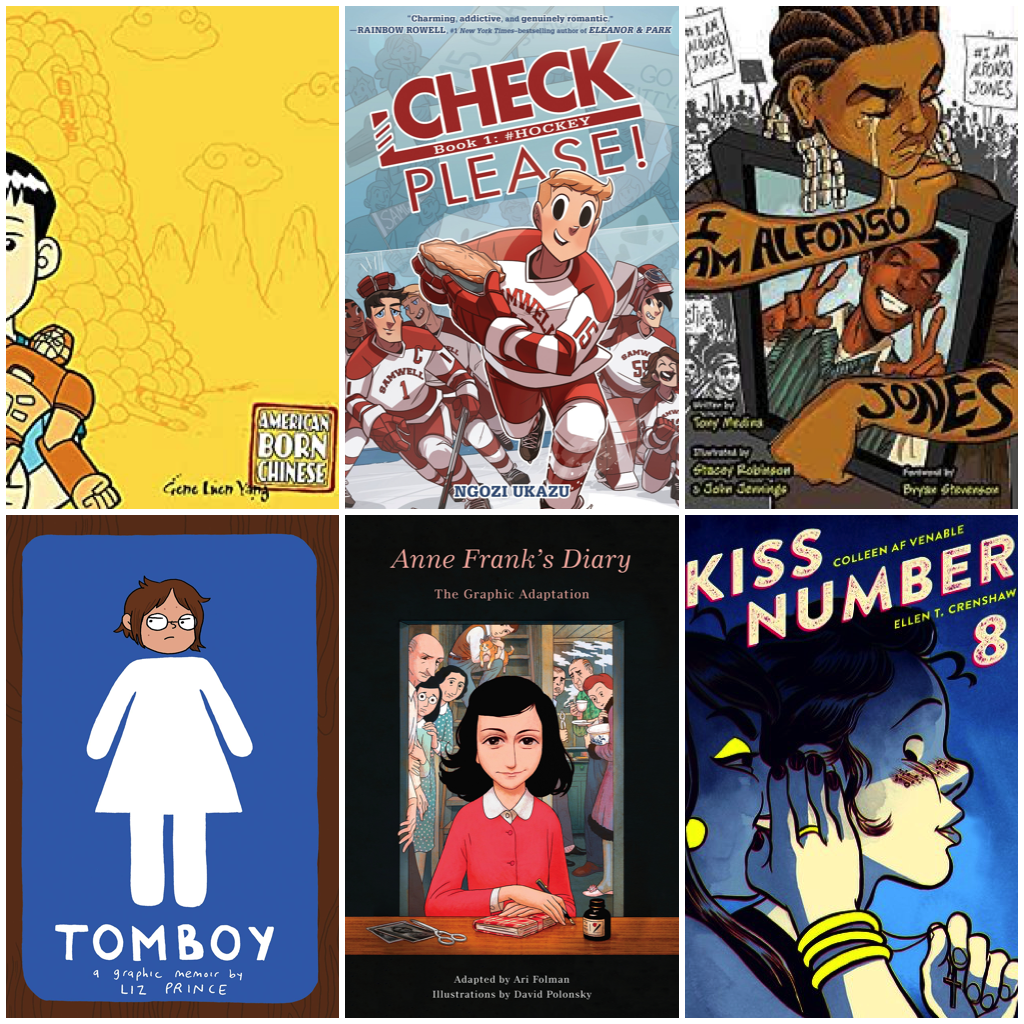

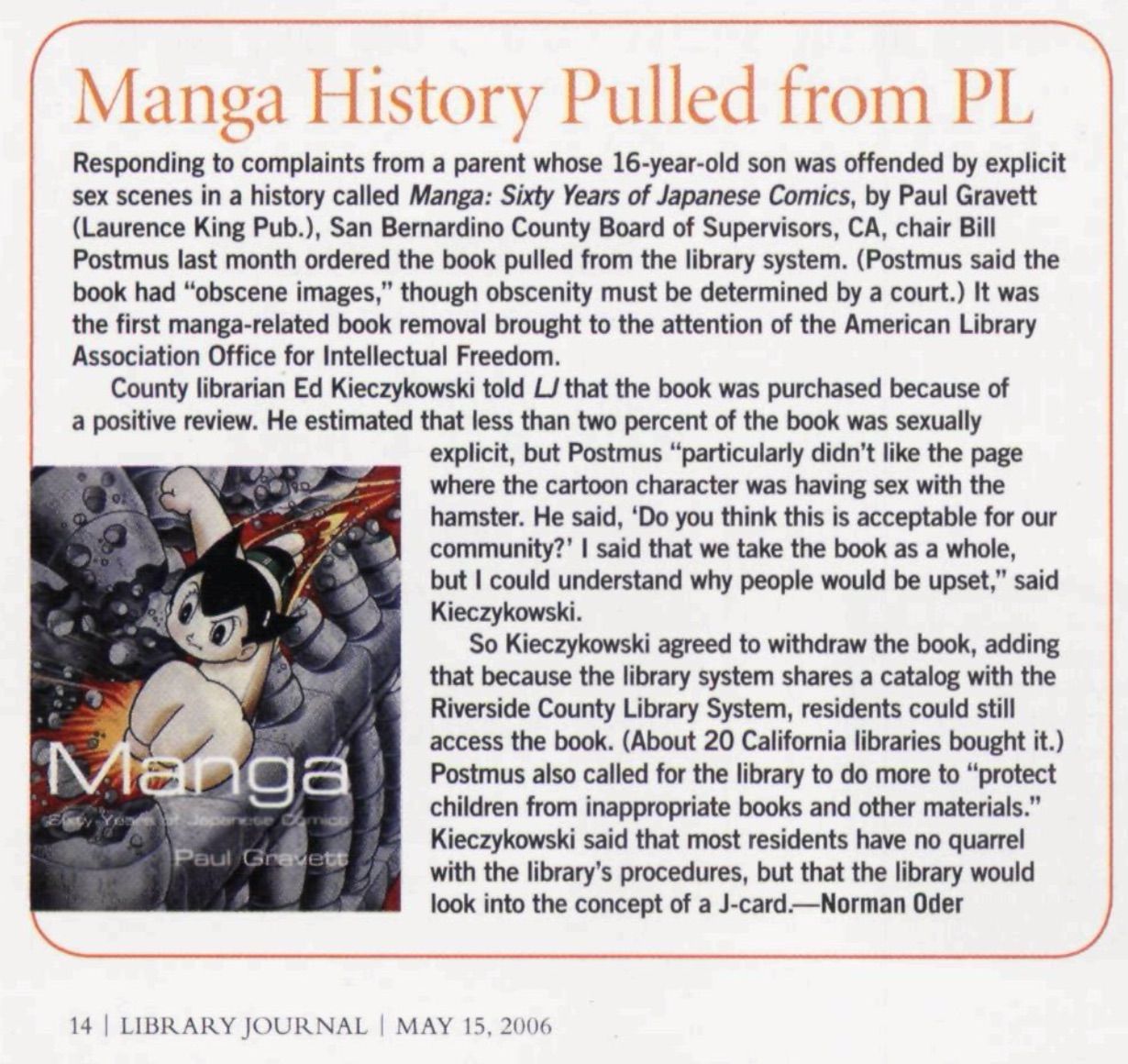

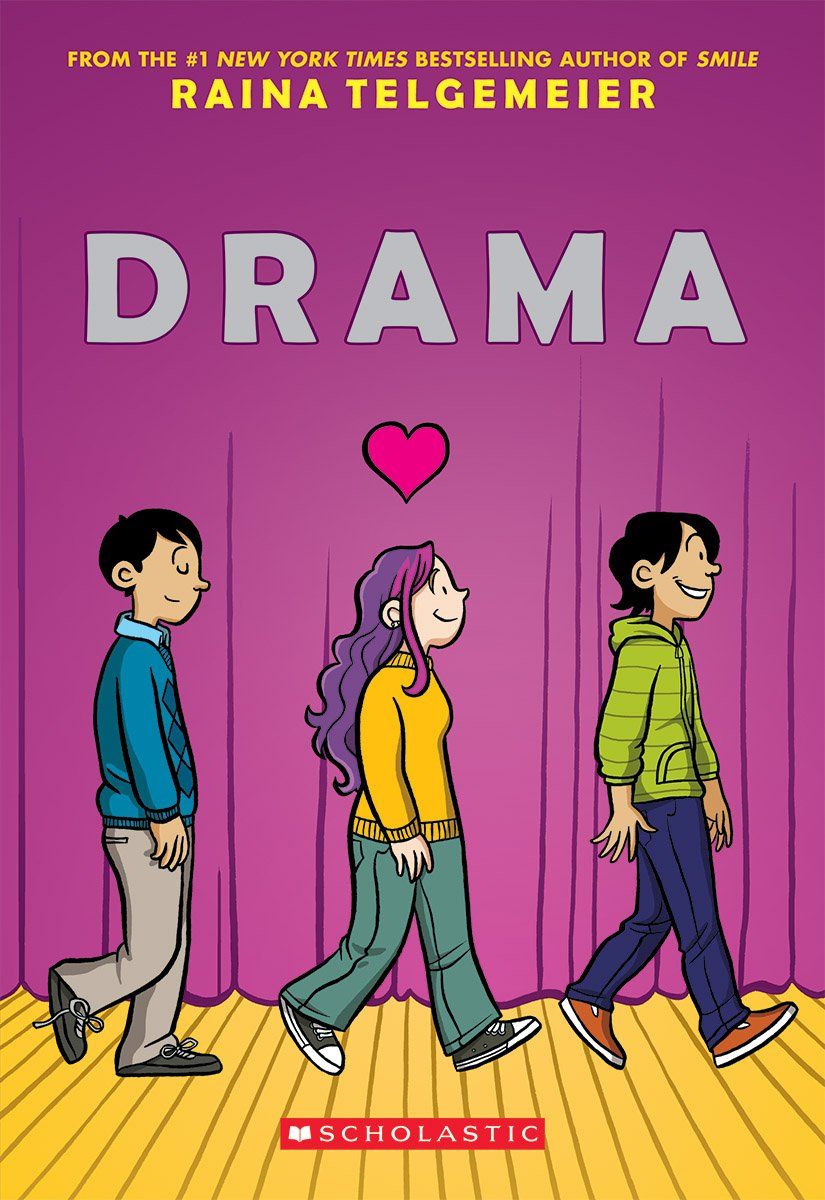

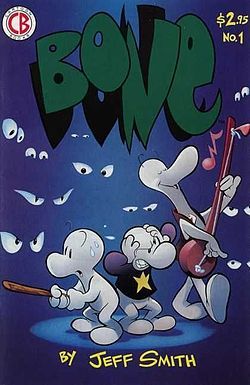

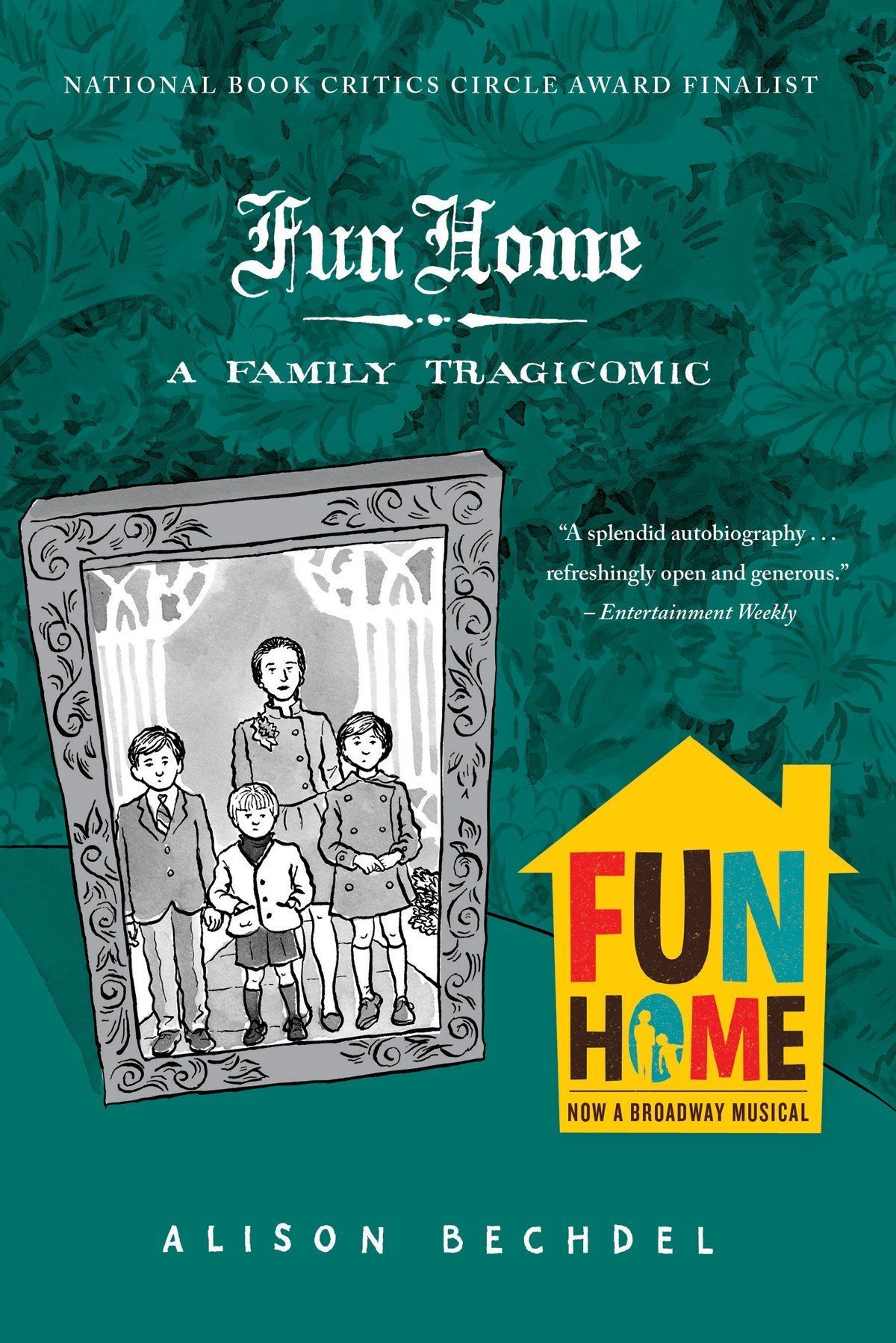

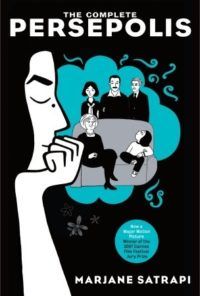

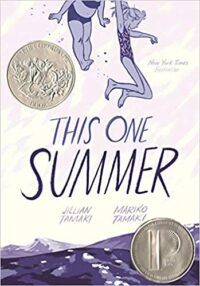

Comics continued to be the target of censors, as well as legal prosecution. When Friendly Frank’s comic shop in Lansing, Illinois, came under fire after a police officer deemed the owner to be selling obscene materials, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund developed and has since helped support comics creators, sellers, librarians, educators, and readers in protecting their right to access comics. The officer, Anthony van Gorp, utilized the dog whistle of the ’80s, claiming that in addition to obscenity, the shop was selling material of the satanic influence. Though comics has been a part of the American literary landscape for well over 100 years, it was not until the early 2000s when more comics began to make their way into schools and libraries. Many were, of course, of the superhero variety, but as comics became more widely accepted as a legitimate form of reading and literacy, more comics beyond the superhero worlds emerged. The late ’00s and early ’10s were especially vibrant times for comics for young people, and as such, censors made their voices heard, challenging and banning comics. Many who challenge comics in today’s era do so from a place of misunderstanding how comics work. As will be seen in the case studies linked below, adults often talk about how children have accessed a comic that looked like a kid’s book and found something that was less suited to their age. Though comics enthusiasts, librarians, and educators have pushed to better educate people about comic literacy — a skill set separate from but related to print literacy, as it involves understanding the purpose of and meaning behind the use of images to tell a story — it is a skill set. As such, it is something censors can use to further their agenda. Anything with images is seen as material for children, despite the reality that many of the titles are published for adults and shelved with adult books. From 2000 to 2009, the American Library Association — which at the time had a much more robust staff and budget dedicated to intellectual freedom — identified zero comics among their top 100 most challenged titles. This makes a lot of sense; the format was still evolving. The story from 2010-2019, however, is different. Despite what was happening in libraries, with a rise in understanding of literacy and its myriad forms and a collection mirroring this, so, too, came the backlist from small but vocal minorities about how comic books were inappropriate. Many of the calls mimicked those of earlier censors, citing satanic influences, inappropriate content (read: sex and sexuality), and being “anti-family,” “unsuitable to age,” or “offensive political viewpoint.” In that decade, 11 of the top 100 most challenged books were comics. Comics challenges and bans have only increased since ALA’s last report. During this current wave of censorship, it comes as little surprise comics are a focal point and in particular, comics that explore gender and sexuality. Drama and This One Summer, published for the middle grade and young adult audiences respectively, foreshadowed the current spate of censorship against queer books; they remain among the titles challenges and banned, though censors have expanded their targets, too. Gender Queer, a coming-of-age memoir by Maia Kobabe, remains at the top of the list for most challenged book this year. It is Kobabe’s own tale of learning to understand eir gender and the struggles to define eirself in a binary world. But rather than consider the story from its literary perspective and appropriateness for young readers who themselves are struggling understand themselves or others in the world, censors have delighted in blowing up two passages from the book without context. Those passages show on-page sex fantasies that are not only not lewd nor obscene, but they are common experiences of young people around the world. It is a clear and willful misreading. It is also a sign that, despite how much time, effort, and energy goes into comics literacy, a small group of well-funded, politically-fueled individuals will continue to showcase their illiteracy. Because in addition to pushing for the right to determine what other people can read, censors today highlight how little they respect art, how little they understand comics, and how eager they are to continue being ignorant about both. Because ALA’s compiled lists of challenged and banned books do not yet include the 2020s and because they do not release the titles of every book challenge they hear (instead releasing their top 10 lists annually), knowing the full scope of current comics challenges is tricky. But thanks to Dr. Tasslyn Magnusson, who has been tracking every title challenged across the country since last fall, it is possible to get an idea of how widespread comics censorship is right now. Between October 2021 and August 2022, there have been at least 40 unique comics titles challenged. This includes at least 80 unique challenges or bans to Gender Queer, 25 to This One Summer, and about 20 each to Drama, Mike Curato’s Flamer, Cathy G. Johnson’s The Breakaways, and Fun Home. Every one of these comics was banned or challenged due to LGBTQ+ themes. It is impossible not to see the trends, even for readers who may not be familiar with comics. These books are queer, they are by or about people of color, and they are about immigrants.

Gender Queer This One Summer Drama Flamer The Breakaways Fun Home The Handmaid’s Tale (Graphic Novel) by Margaret Atwood and Renee Nault New Kid by Jerry Craft Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me by Mariko Tamaki Class Act by Jerry Craft Check Please by Ngozi Ukazu Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by J.P. Stassen Kiss Number 8 by Colleen AF Venable and Ellen T. Crenshaw Maus by Art Spiegelman The Magic Fish by Trung Le Nguyen Tomboy: A Graphic Memoir by Liz Prince V For Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd Anne Frank’s Diary (Graphic Adaptation) by Anne Frank, Ari Folman, and David Polonsky Brazen by Penelope Bagieu I Am Alfonso Jones by Tony Medina Losing the Girl: Book 1 by MariNaomi Maus 2 by Art Spiegelman My Friend Dahmer by Derf Backderf The Witch Boy by Molly Knox Ostertag American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang Delicates by Brenna Thummler Fairy Tail, Volume 45 by Hiro Mashima Go With The Flow by Karen Schneemann and Lily Williams Hey Kiddo by Jarrett J. Krosoczka Lighter Than My Shadow by Katie Green Moonstruck, Volume 1: Magic to Brew by Grace Ellis, Shae Beagle, and Kate Leth Persepolis Saga Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery The Authorized Graphic Adaptation by Miles Hyman The Fire Never Goes Out by ND Stevenson The Prince and the Dress Maker by Jen Wang They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, Harmony Becker Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed by Laurie Halse Anderson and Leila del Duca Y: The Last Man by Brian K. Vaughan, Pia Guerra, Jose Marzan Jr., and Jose Marzan

Censors Love to Target Comics Like Maus. Here’s Why from Washington Post Comics Grapple with Bans Amid Growing Culture Wars at the San Diego Union Tribune American Comics Self-Censorship Comics Code from New York Public Library Comic Books, Censorship, and Moral Panic from Princeton University’s Mudd Manuscript Library A History of Comics Censorship at CBDLF How American Paranoia Ruined Censored Comic Books at Vox (content advisory for ableist title) The National Organization for Decent Literature: A Phase in American Catholic Censorship by Thomas F. O’Connor, accessible via JSTOR. (This in particular ties into recent moves by CatholicVote to remove queer books from public libraries). Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-comics Campaign edited by John A. Lent International Journal of Comic Art

These are just the tip of the iceberg.

![]()