Nancy remains internationally popular with every new generation, with her book series having been translated into over 45 languages and having sold over 80 million copies worldwide. She’s made the leap from page to screen multiple times, and her popularity and influence have spawned countless spin-offs and inspired numerous other fictions featuring female detectives. But most interestingly, Nancy Drew serves as an intriguing look into how traditional gender roles surrounding masculinity, unlike the character’s timeless influence, have remained particularly stagnant. Nancy Drew was the brainchild of children’s book mogul Edward Stratemeyer, who dreamed up the character as a female counterpart to his Hardy Boys series, which featured teenage boys who solved mysteries. Through the Stratemeyer Syndicate, which was a producer of a number of dime-novel series for children in the 20th century (or “penny dreadfuls” as they were previously known), both series were ghostwritten by several different writers employed by the Syndicate and published under the pseudonyms Franklin W. Dixon for the Hardy Boys and Carolyn Keene for Nancy Drew. By the mid-1930s, both series were incredibly popular, but Nancy Drew stood out because never before had young girls seen themselves represented in the way that Nancy Drew was in children’s literature. Even in the earliest installments, she was bold but still polite, feisty but never rude. The early popularity of Nancy Drew also made publishers realize that there was a market for books that had not previously been catered to: young girls. Before Nancy Drew took off, publishers—including Stratemeyer—believed that young girls weren’t even an audience worth catering to, since many of them had shown themselves to be perfectly happy to borrow “boy books” from their brothers to fulfill their sense of adventure. As Stratemeyer once observed, “Almost as many girls write to me as boys and all say they like to read boys’ books (but it’s pretty hard to get a boy to read a girl’s book, I think.)” While Nancy Drew has evolved with time and shifting social norms, it appears that—nine decades after Stratemeyer wrote these words—masculinity and gender norms for boys have not. In June 2007, I was in my last week of third grade. As a treat, my mom took me to the theatre on a weeknight to see a movie: the new film adaptation of Nancy Drew, starring Emma Roberts. Being regular moviegoers, we had seen the preview a few months before and I had immediately expressed my eager excitement. I had never read Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys, but I was well aware of who they were. Having been an avid reader as a child, my parents told me all about how popular both series of mystery books were when they were young (several decades after their initial boom), and how my mother in particular loved to read Nancy Drew books growing up. “Nancy Drew was for the girls, and the Hardy Boys were for the boys,” she said. She never gave this gendering of children’s books a second thought, but I did. By this point, already struggling to fit the masculine ideal for boys, I was acutely aware of where I was told I should fit in, and my overachieving personality would in turn try everything to make sure I accomplished it.

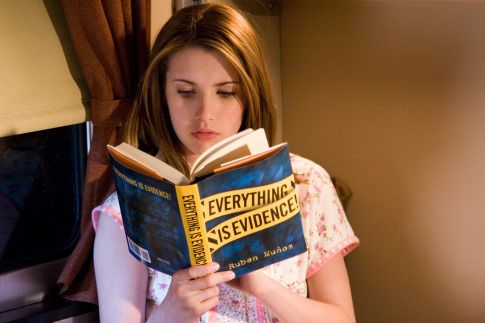

For months after that first screening of the Nancy Drew film, I was obsessed with her. I took one of my mom’s old purses and made my very own “sleuth kit,” complete with magnifying glasses and BAND-AIDs, and would act out mysteries in the backyard by myself when I thought nobody was watching (translation: I was very gay.) I wanted so badly to start reading the Nancy Drew mystery books, since I loved reading, but I had already internalized the gendered notion that Nancy Drew was strictly for girls. If I wanted to read mysteries, I should read the Hardy Boys. Nobody ever specifically said these words to me—I had just inferred from others all of the ways I should try to fit in. So in 5th grade I picked up a Hardy Boys book and was determined to love it. I hated it, but I forced myself through every word. And while I’m still mad at myself for forcing myself through a book I actively remember hating, it taught me something about myself (which I would later learn again working in retail): I’m very bad at pretending to care about things that I don’t care about. I didn’t care about the Hardy Boys. I cared about Nancy Drew. Later that year, my aunt—who was so fed up of watching the movie with me and hearing me ask her if she ever read Nancy Drew as a kid—bought me a shiny new set of Nancy Drew books. The Stratemeyer Syndicate was bought by Simon & Schuster in the 1980s, which ensured that Nancy was still widely available to young readers well into the 21st century. Still, I couldn’t bring myself to get through them. And while it might have had something to do with the fact that I’ve always had a reading level way above my age bracket and I was probably just bored by the adventures of Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, it had more to do with the fact that, at 11 years old, I was already experiencing and internalizing displays of toxic masculinity. Nancy Drew was for girls—why on earth would I, a boy, want anything to do with her? As Liz Plank notes in For the Love of Men: A New Vision for Mindful Masculinity, “If there was nothing wrong with femininity, no one would be worried about men exploring it. In other words, the reason why we as a culture are scared of men acting like women is because we diminish the feminine.” It represented the start of a power struggle between myself and the world that would continue for years to come. It explained why I always identified a little too strongly with the lyrics of “Reflection” from Mulan: “When will my reflection show who I am inside?” Despite it all, to this day I’ve never stopped watching the Nancy Drew film with Emma Roberts, which remains an all-time favorite. I own a physical copy of the original motion picture soundtrack, and can recite it to you backwards and forwards. As I grew up and started to see the narrow-minded, playground gendering of everything children touch a little more clearly, I realized why I identified so strongly with Roberts’s version of Nancy Drew, who moves from her small midwestern town of River Heights to Los Angeles, where she promises her father that she won’t sleuth anymore. She promises to stop and just be a “normal teenager,” but she can’t: after a cruel prank at the hands of her high school peers, she realizes that the sleuthing world is the only place where she fits in. For the longest time, I didn’t really have a place where I felt like I fit in, but whenever I watched movies like Nancy Drew, I felt better—because I knew she didn’t fit in for just being who she was, either. Ironically, Nancy becoming a misfit in the 2007 film was a bone of contention with most critics, who criticized taking the character out of her midwestern town where she was always the celebrated hero and dropping her in urban California to be mocked and bullied. In fact, none of Nancy Drew’s screen adaptations have ever been very well received—from the first Warner Brothers film adaptations in the 1930s to The CW’s most recent teen drama adaptation—since it seems that no audience wants to accept someone else’s version of what Nancy Drew looks like or how she behaves. She’s been around for so long that she exists individually in each reader’s imagination, making it virtually impossible to satisfy everybody at once. In her book Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her, Melanie Rehak writes, “A role model for millions of girls, [Nancy Drew] has always been that most elusive, more essential thing as well: a trusted companion.” And I can only assume that Nancy has also been a trailblazing role model and trusted companion for other boys like me, who grew up dodging toxic masculinity at every turn and confused by the deeply conflicted gender roles presented to him, and who interpreted Nancy Drew as representing the ability to be whoever you want to be.