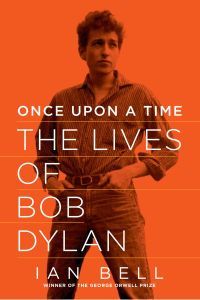

I’ve been thinking a lot about biographies lately. For several years now, I’ve been reading and listening to one after another, trying to understand how great historical figures (musicians, presidents, scientists, artists) are products of/influence their times. With each book I’ve wondered, “what does it mean to be so amazing that books are written about you long after you’ve died? What does it mean when a single person’s life spawns twenty competing biographies?” Mozart, Darwin, Elizabeth I, Dreiser, Adams, Emily Post: I’ve now incorporated each of these individuals into my attempt to make sense of history and the world that I am a part of at this moment. Each biography, of course, is slightly different, for every author has his/her own philosophies, not just about a particular person’s life but how to write about that life. For instance, McCullough’s John Adams gave me the distinct impression that the author was preeeeety partial to his subject. John comes out smelling like a rose. Jefferson does not. Neither do Franklin or Hamilton. In fact, the only other figure who isn’t battered by McCullough’s pen is Abigail. And so, it was with intense interest that I launched into the latest Bob Dylan biography*. I had so many questions up front: what would it be like to read a biography of a person who is still alive (something I hadn’t yet done somehow)? How does anyone write about such a perplexing and changeable individual as Bob Dylan? How many other biographies have been written about him and what does this one tell us that we don’t already know? (to answer this last question here: there are boatloads of Dylan biographies, stretching from the late 1960s all the way into next year).

I could see from the beginning that Bell was not writing your run-of-the-mill bio: you know, “dude was born in X, dude went to school at X, dude had issues with his mother/father/siblings/classmates, dude struck it big in X doing X…” Nope. This particular Dylan biography is often as “freewheeling” as Dylan’s second album: cinematic at times, analytical, biographical, philosophical. I say “cinematic” because the opening chapter gives us flashes of Dylan in Manchester 1966 after he had “gone electric”- we see him in different moments, each moment fleshed out with later moments and earlier moments, all in an attempt to capture what could have led to audience members thinking that Dylan had betrayed them. They wanted to own him, Bell explains. They wanted to see reflected back at them what they expected from the Bob Dylan they knew. But, and this is the question that sustains and drives this book: WHICH Bob Dylan? Because there were/are many. Once Upon a Time: The Lives of Bob Dylan makes an argument, like many biographies inevitably do, but here the argument is just as important as the subject. Everything that can be known by someone who isn’t Bob Dylan has been mined to exhaustion. Dylan experts and fans have tracked down the singer’s family, girlfriends, first recordings, scraps of songs, everything. Dylan, though, is a master of illusion, “reinventing” himself, as Bell maintains, because this is (paradoxically) who Dylan is. His identity and his music are both fluid and elastic. At one point, Bell explains that “Dylan is lauded as one of the most original artists of the age and accused, simultaneously, of relentless plagiarism. So what if both claims are true? And would music be better off if Bob Dylan had never borrowed?” (241). We have here a problem facing any human “creator”: how much of what they are doing is original and how much was taken from someone else? For some reason, we like to think that someone as talented and wide-ranging as Bob Dylan is wholly unique, one of those people specially put on Earth to push our music/science/art/philosophy forward. But Dylan, like every creator, comes from somewhere. He has stated that he grew up feeling like he was born in the wrong place: the fact is that Robert Allen Zimmerman was a Jewish boy from Hibbing, Minnesota; another fact is that Bob Dylan shed this identity the minute he had the chance. He learned his craft from the blues and folk, quintessentially anonymous genres where tunes and words were passed down and around often without clear attribution. Everyone borrows because, as we know, nothing can come from nothing. For all that, though, Dylan forged something different, something that set him apart from other singers of the ’60s: his high but raspy voice, his intonation, his talent for musical absorption and reinvention, his confidence in his own art and his recognition that no artist can create masterpieces forever. Bell captures all this with wit and patience, at once carefully analytical and then merrily philosophical. He even stops at the 1970s, presumably because it’s not this book’s job to note down every single event in Dylan’s life up to and including the present. It would be out of date immediately upon publication. Rather, Bell leaves us with a sense of a life and how it was lived. And it’ll send you to Dylan’s albums and documentaries like Scorsese’s No Direction Home. Good biographies, I’ve always felt, should make you want to keep learning and thinking about their subjects. In this way, the biographer bestows immortality.

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise. To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.