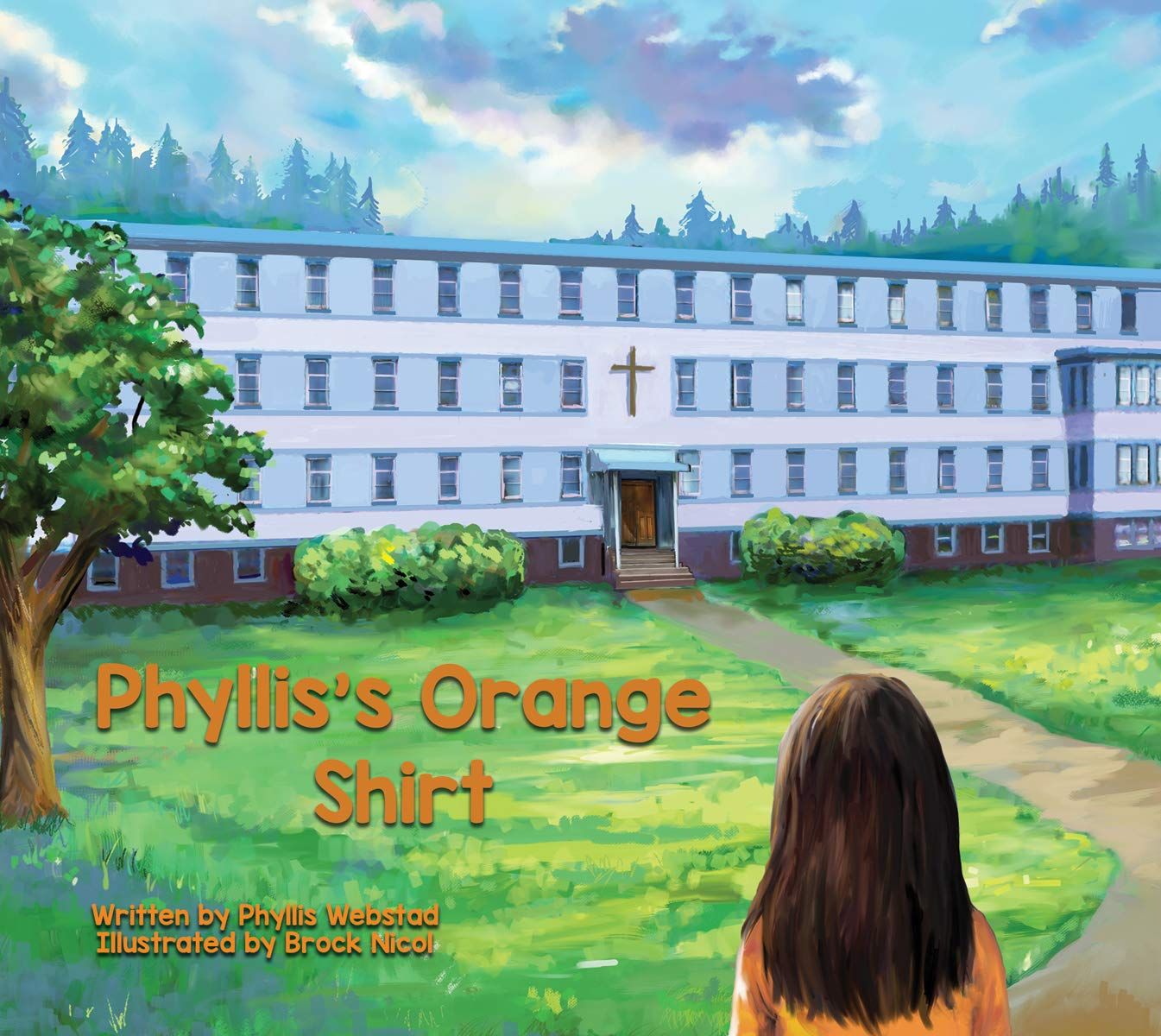

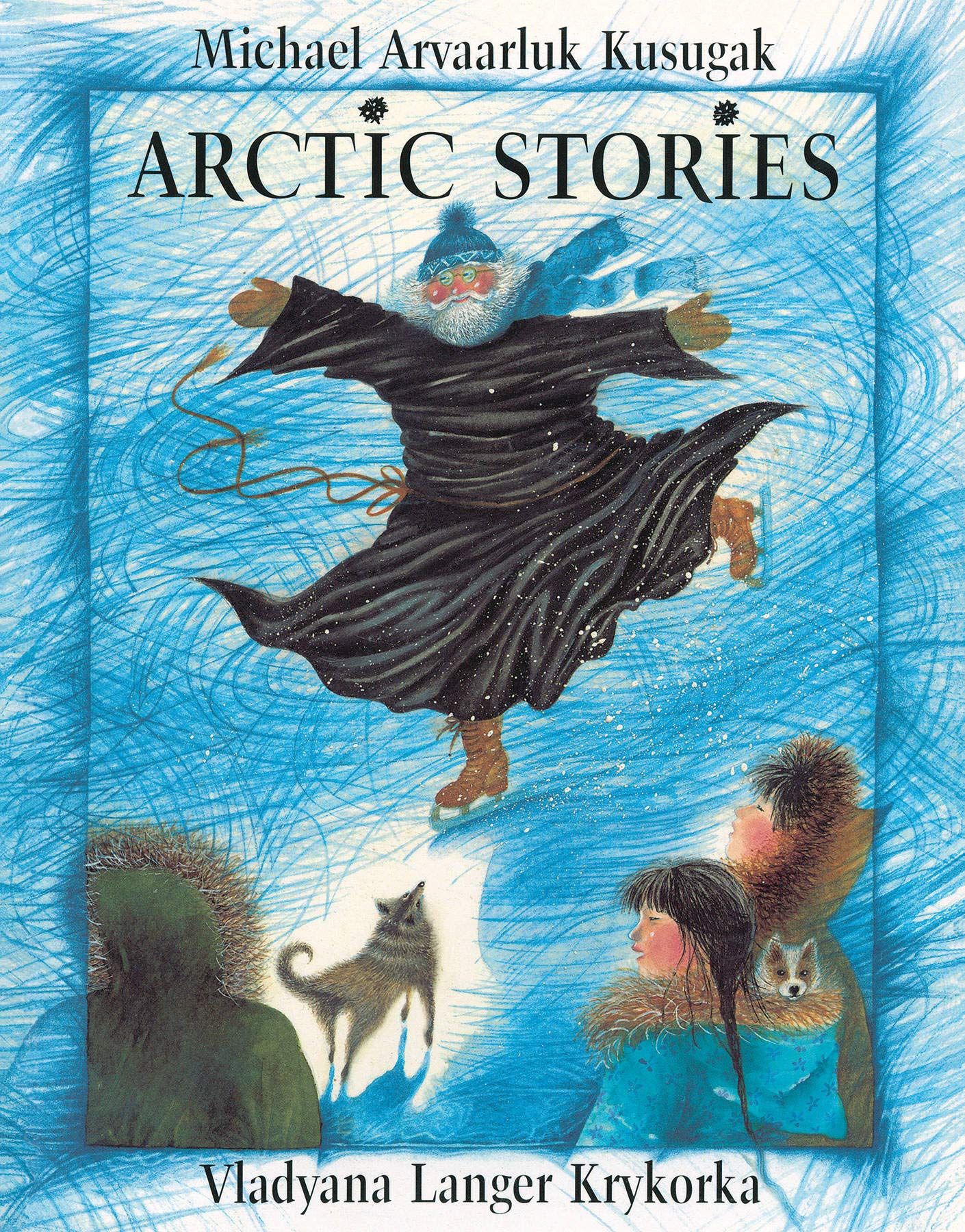

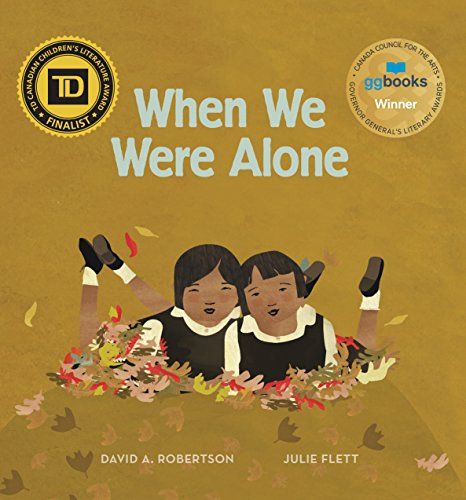

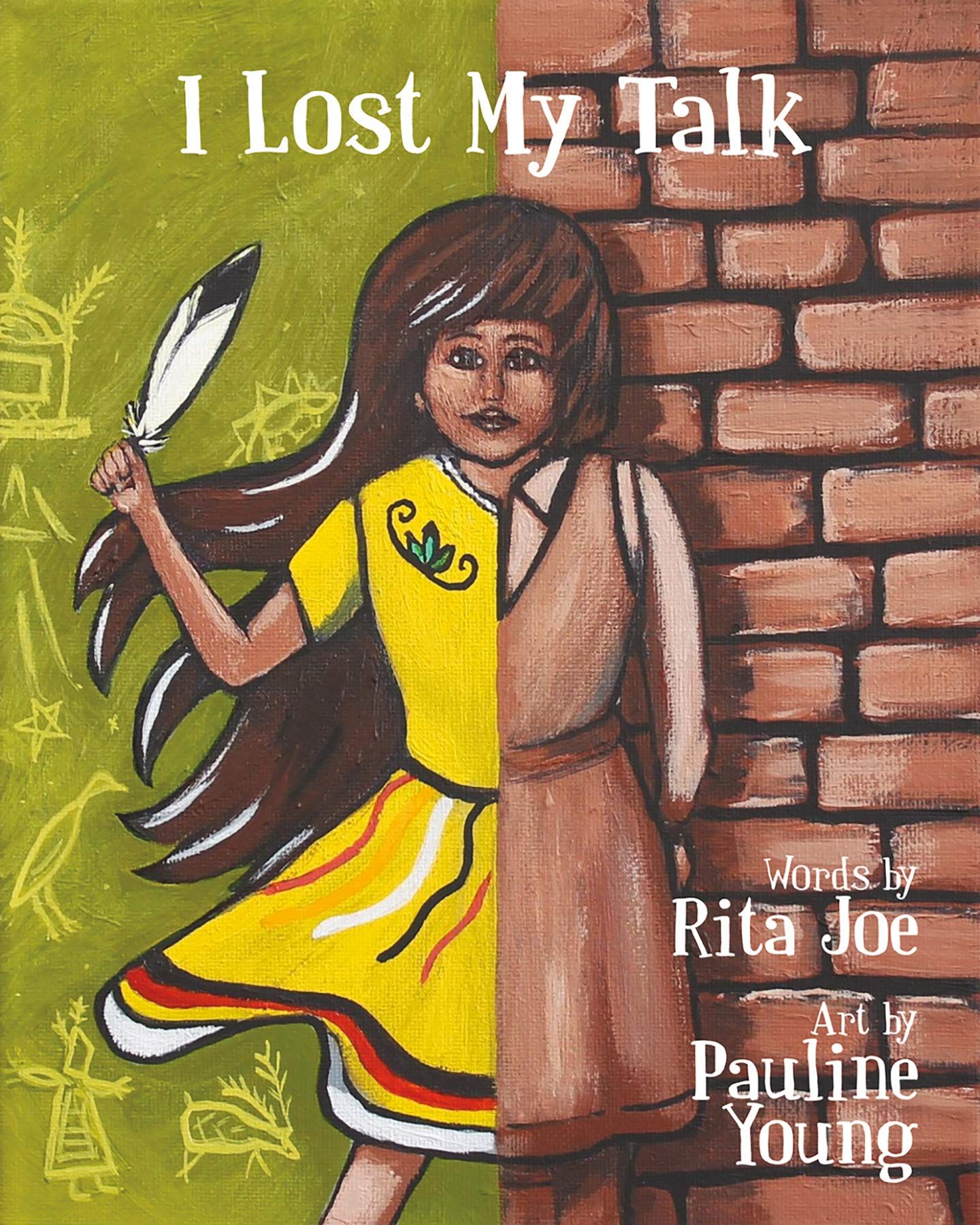

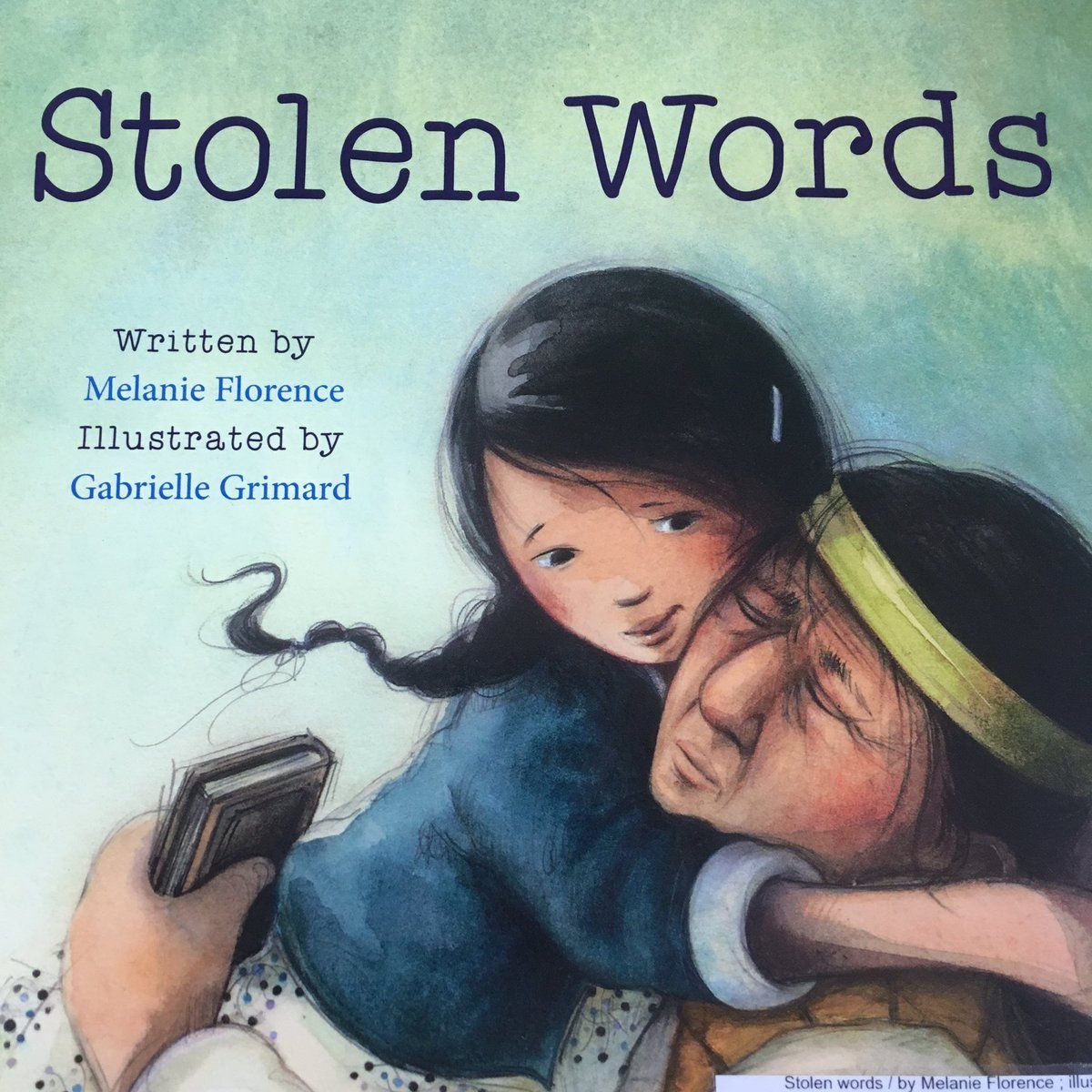

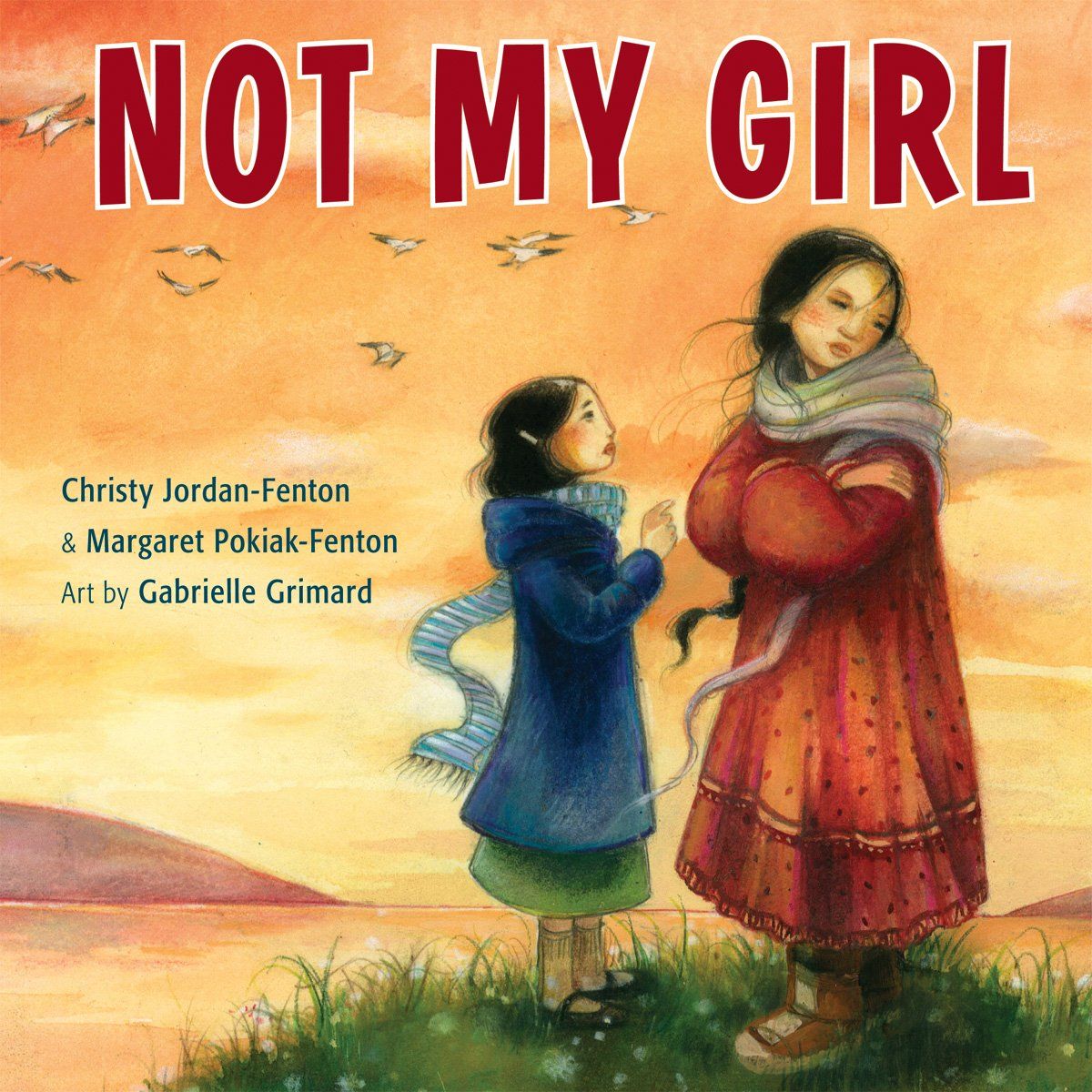

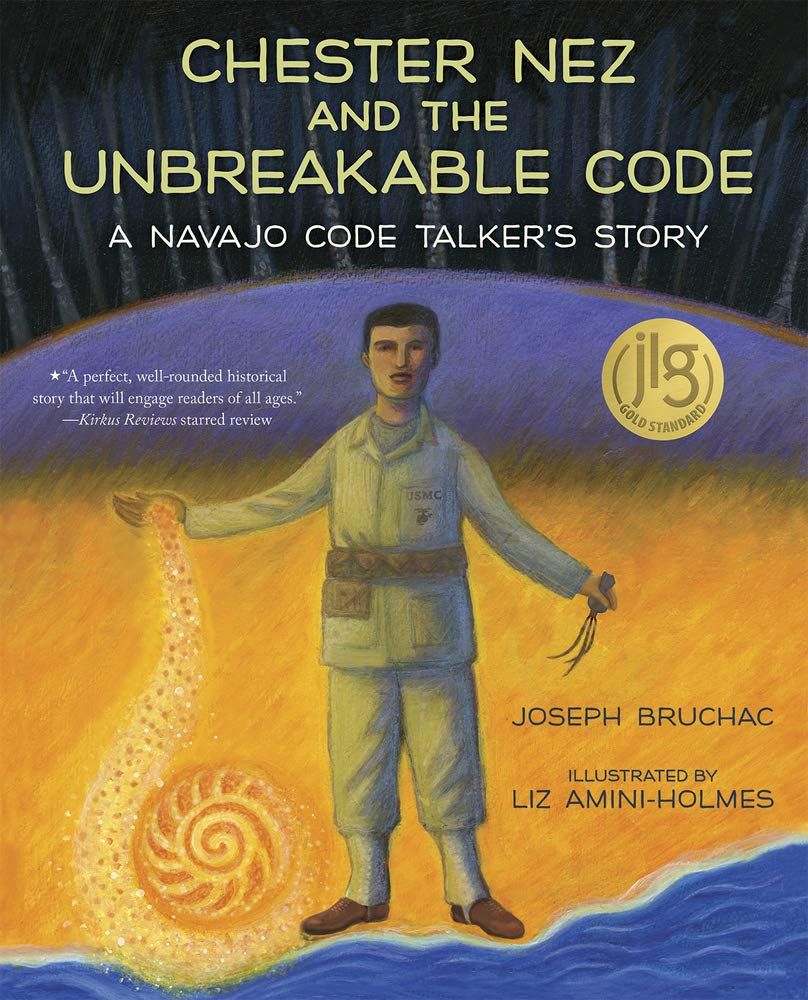

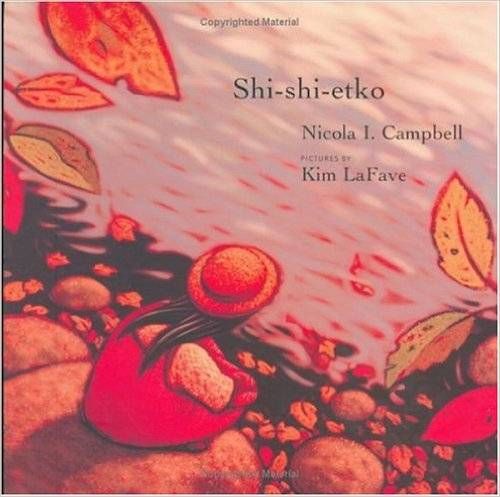

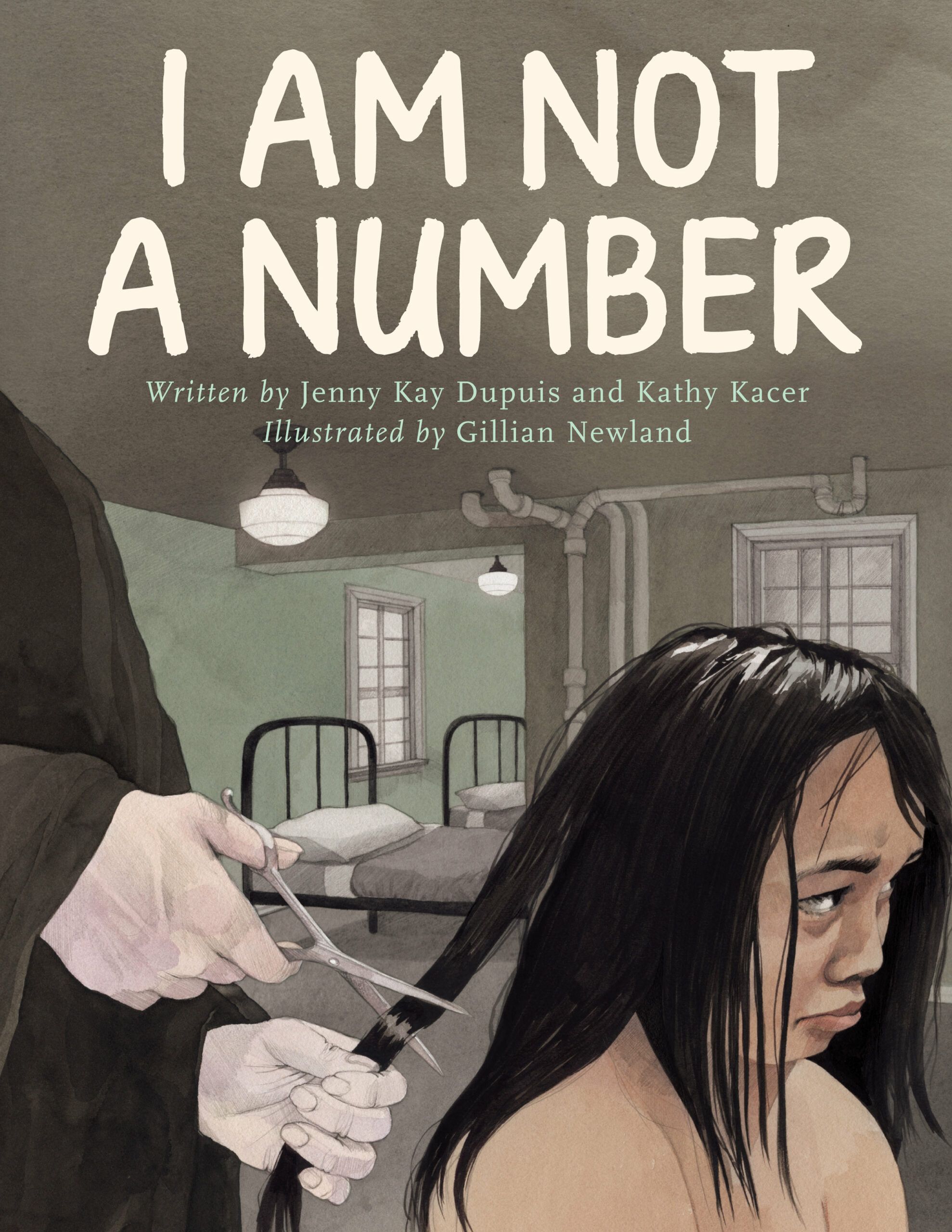

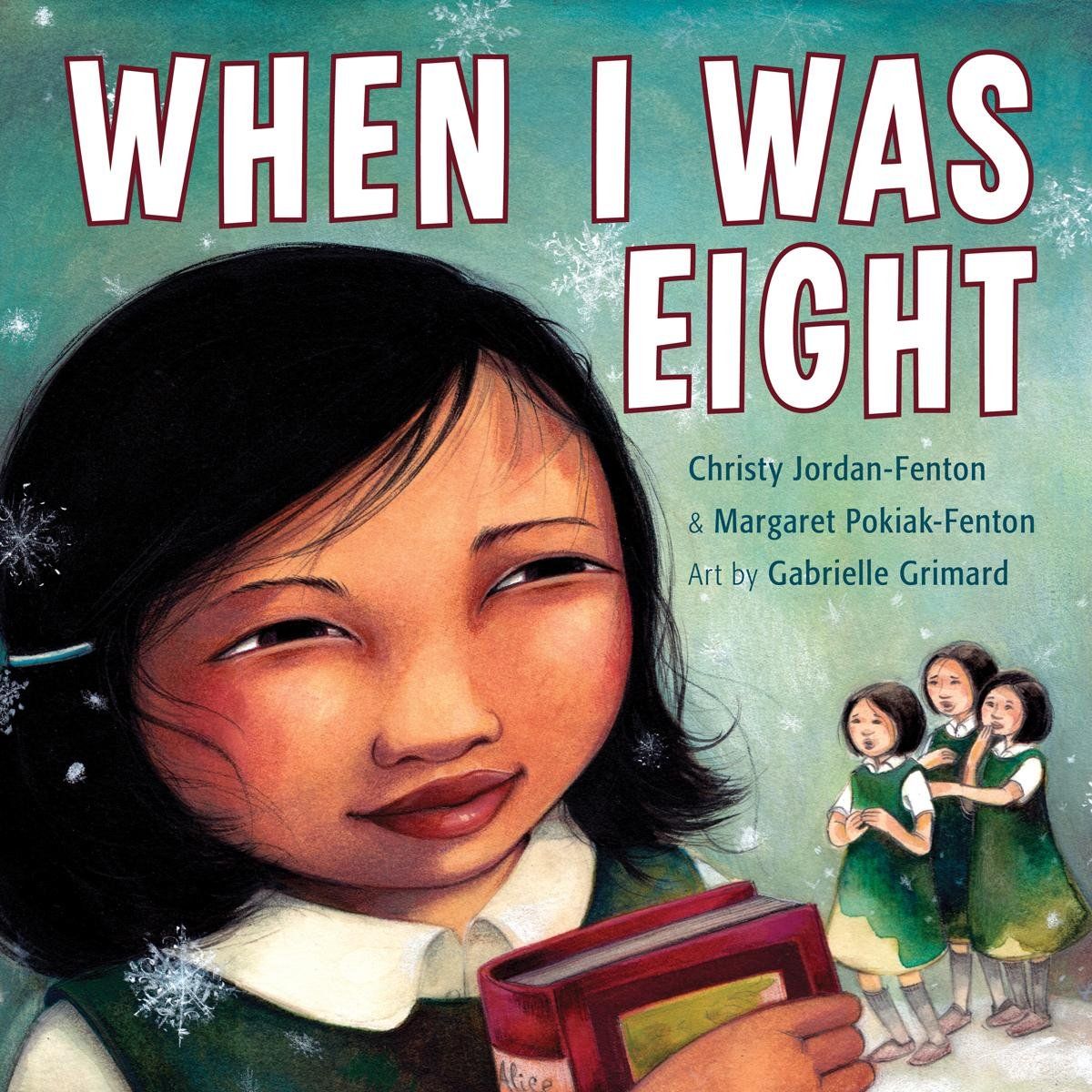

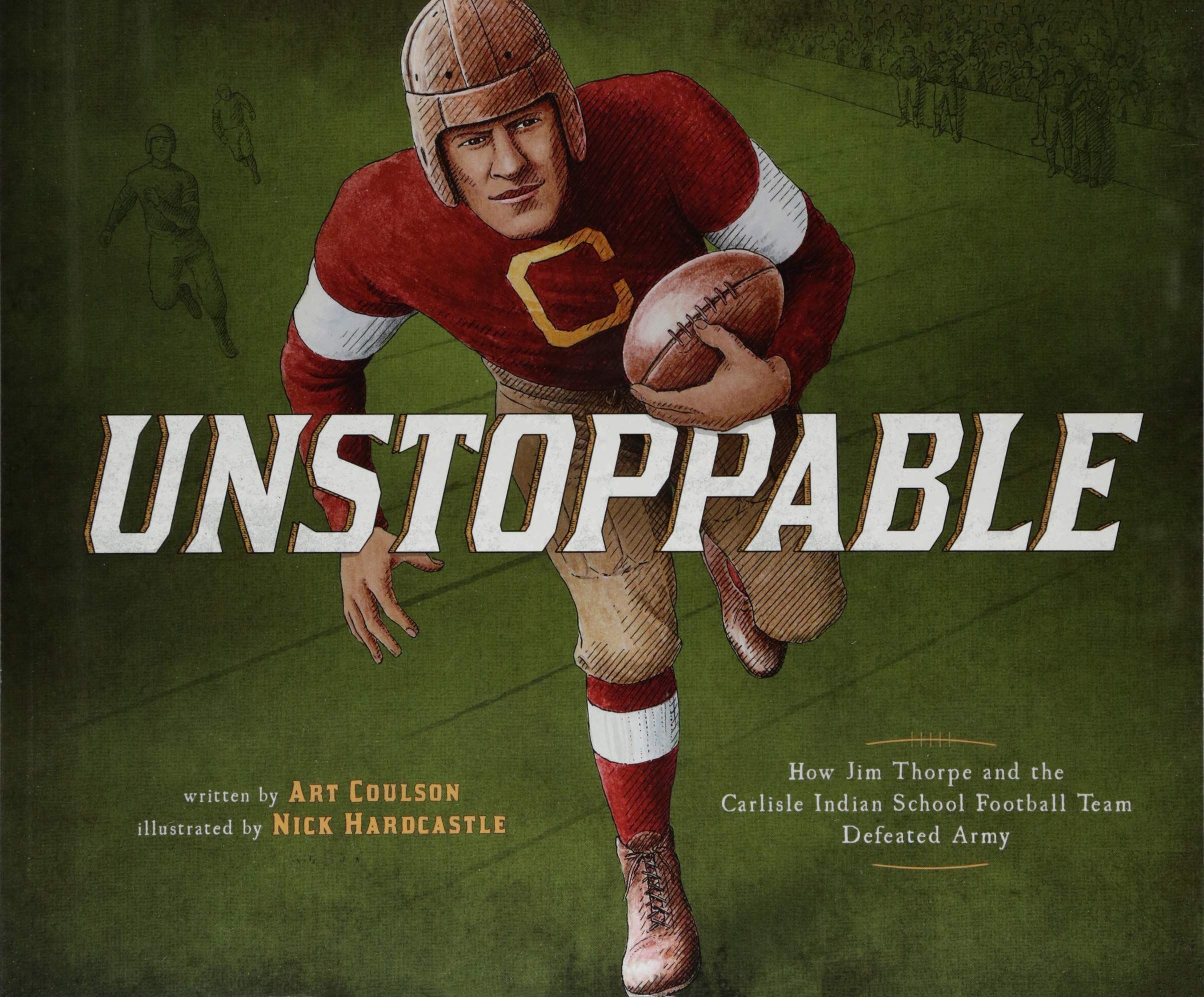

There’s also a difference between what’s technically in the curriculum and what is actually being taught — and how. Whether you are a parent or a teacher, teaching children in your care about this history is essential, because you can’t assume someone else already has or will in the future sufficiently. The repercussions of residential schools are being deeply felt by generations today, and education is one small piece of how we can grapple with this. In this post, I will highlight a few picture books that can start conversations about residential schools with kids. I also have a list for adults: Books About Indian Residential School In Canada: Nonfiction and Fiction. I want to preface this by saying that I am not an expert. I am not Indigenous. The best way to make sure you are being respectful and getting accurate information is to make connections with your local Indigenous nations. For example, the Native Friendship Centre in my city has a library that is open to anyone (for $1 a year membership), and they are happy to give recommendations, whether you have no idea where to start or want to dive more deeply into a specific research area. I also recommend checking out the First Nations Education Steering Committee, especially if you’re in British Columbia. They have a page for authentic First Peoples resources, and they also have free in-depth lesson plans for teaching English First Peoples. There’s also Strong Nations, an Indigenous-owned online bookstore with a huge catalogue to help you find more titles. Usually, we link titles using affiliate links, but I invite you to find an Indigenous-owned bookstore to order these from. I’m a personal fan of Iron Dog Books, but here is a list of more across the U.S. and Canada. If you want to read adult books about residential schools, here is a list of history books, memoirs, novels, and poetry that tackle Indian residential schools in Canada. This is an adaptation of her story suitable for young readers, with a sentence per page and age-appropriate content. She also has a middle grade version of this story called The Orange Shirt Day Story. Phyllis Webstad is Northern Secwpemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (Canoe Creek Indian Band). Michael Kusugak is Inuit. David A. Robertson is Swampy Cree and Julie Flett is Cree-Métis. Published simultaneously was I’m Finding My Talk by Mi’kmaw activist and spoken word artist Rebecca Thomas, also illustrated by Pauline Young. In this companion picture book, Thomas discusses rediscovering her community and culture as a second-generation residential school survivor. Rita Joe and Pauline Young are Mi’kmaw. This title also has a teaching guide for grades 1–4. Melanie Florence is of Cree and Scottish heritage. Margaret Pokiak-Fenton is Inuit. (Christy Jordan-Fenton is her daughter-in-law.) Joseph Bruchac is a Nulhegan Abenaki citizen. There is an accompanying short video available on YouTube as well. Nicola I. Campbell is Interior Salish/Métis. Jenny Kay Dupuis is of Anishinaabe/Ojibway ancestry and a member of Nipissing First Nation. Margaret Pokiak-Fenton is Inuit. (Christy Jordan-Fenton is her daughter-in-law.) Art Coulson is Cherokee. I invite you again to purchase these books from an Indigenous-owned bookstore if possible. The impacts of residential schools are long-lasting. Donate to the Indian Residential School Survivors Society and Orange Shirt Day to help heal survivors and their families and educate others about Canada’s continuing legacy of genocide.