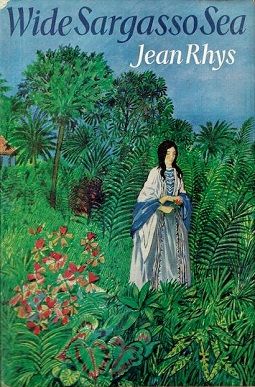

But the professor, a newly-minted PhD in her first official position, had other ideas than the usual Dickens to Wilde and on through the drawing room dramas of British literature. Instead, she decided to teach us a visceral lesson on the legacy of Jane Eyre by choosing works that are based — directly or loosely — on Brontë’s seminal tale. We spent the entire semester looping book after book back to Jane, to the madwoman in the attic and physical manifestations of inner turmoil, to disapproving aunts and dead best friends. I’ve been thinking about that class for almost 20 years, and have used it as a jumping-off point for many animated discussions about how all art is intertwined, and if you look at it from a certain angle, everything is art. To borrow a phrase: Reader, it blew my mind. What is it about Miss Eyre that keeps us coming back to her story? Personally, I will never pass up a strong female character, and Jane’s particular brand of iron-clad will is immensely satisfying. Everyone underestimates her at every turn, and yet she simply continues forward, doing what she believes is right and necessary. She believes in herself, wholly and without reservation. While there are valid arguments to be made that Jane Eyre’s fate is a somewhat dismal one — caring for a (wealthy) blind man and being a social outcast for the rest of her days — it is her choice to do so that ends the tale. She marries him, and not the other way around. The continual retellings and re-framings of Jane’s story — as well as the stories of the characters around her — prove to me that we will never have enough stories of determined young women in this world. And so today I am going to discuss the high points of the syllabus of that surprisingly fateful class, along with a couple of newer retellings to round out the list. Consider this a companion piece to this awesome roundup of Jane Eyre retellings wherein I dig in a little further into the “why.” As with any challenge to the cultural expectation of women being submissive to the men in their lives, Jane Eyre was received with no small amount of outrage. It was called “un-Christian” and “lacking moral value.” My readers will not be surprised to learn that it was also an instant best seller. Interestingly, while film versions of Jane Eyre are usually set closer to the publication date, today I was reminded that the actual timeframe of events is 1808–1820, based on references in the text. The story follows her through Rochester’s gaslighting and the shredding of their marriage, with Jane herself never named and only a shadowy fringe character; this is because Rhys understood that Rochester’s sins do not stain another woman, nor is Jane’s ignorance of Antoinette’s existence her (Jane’s) fault. WSS deals heavily with postcolonialism in the United Kingdom, as well as issues of slavery and ethnicity. It is written in a gorgeous, lush, lyrical first person style, at times shifting between Antoinette and Edward as their relationship crumbles. Wide Sargasso Sea requires us to question the relative truth of Jane’s narrative in the original text, as well as Rochester himself as seen through Jane’s eyes. People who have read Jane Eyre in this timeline have always found the ending rather dull and disappointing. Hijinks ensue, the outcome of which is that Thursday takes a job as a LiteraTec, tasked with keeping characters inside literary works in line. It is a romp and deeply, deeply strange, but it is a testament to the enduring legacy of Jane Eyre that an entire series of novels began with a twist on her story.