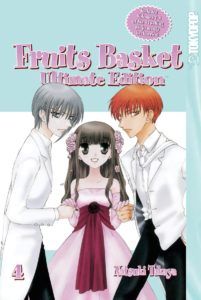

Fruits Basket is a little mix of everything in a long story centring an orphaned teenage girl, Tohru Honda, and the mysterious Sohma family who take her in. Tohru soon realises that the Sohma family are victims of a very specific curse – when they’re hugged by someone of a different gender, they turn into an animal from the Chinese zodiac. It’s an odd hook, and one that is, predictably, the source of many a gag – but as the series unfolds, Takaya teases out a bittersweet tragedy alongside the comedy. Many of the characters, like Tohru, are grappling with loss or grief, while others are dealing with the aftermath of various forms of abuse. As the Sohmas and Tohru adapt to their new situation, they bring out the best in each other, and many of the characters – particularly the two male leads, Yuki and Kyo, who regularly clash throughout the series – reach a mutual understanding and acceptance. There are a few aspects of Fruits Basket that haven’t aged well in the 13 years since the series finished. The setup of the family curse is based around some pretty heteronormative ideas (each cursed Sohma family member is portrayed as romantically isolated because they can’t have close physical contact with someone of a different gender – the idea that they might love someone of the same gender is rarely addressed). There are also a couple of potentially transphobic character portrayals which, while not maliciously done, may be upsetting to some readers. Tohru, the main character, can be read as quite a traditionally self-sacrificing heroine, who often takes on the role of home-maker and mediator between a bunch of unruly men. However, there are also many parts of Fruits Basket that have stood the test of time. Tohru isn’t simply a passive character – instead, she proactively sets out to break the Sohma curse. Alongside Tohru, there’s a large cast of other female characters, with a wide range of personalities, motivations and backstories of their own (my favourite being one of Tohru’s best friends, brash former gang member Arisa Uotani). Fruits Basket is a series that I will always have a strong nostalgic fondness for. The magical realist background, with the hook of ‘characters transform into animals at inopportune moments’, allows Takaya to dig deep into some very realistic, very human dynamics. Over the series, Fruits Basket delves into the death of a parent, the process of getting over a lost love, and the resilience of anyone who’s survived an abusive relationship. Despite the seriousness of these themes, the silliness of the magical premise is never lost, and the overall tone of hopefulness and the power of friendship and chosen family connection resonates throughout. Plus, the animal versions of the characters are consistently adorable. (There’s also a lovely bonus in Natsuki Takaya’s notes throughout the paperback versions, where she talks about everything from the initial serial publication of the manga, to how she names her video game characters, and the satisfaction of eating a large bowl of food after a cathartic crying session). Fruits Basket is a sweet, silly and often emotional story, with characters that I’m still fond of over a decade after I first picked up Volume 1. I love the story’s slow burn, and the way it often makes fun of its own tropes – and I think I’m due a re-read. Want to read more manga, but don’t know where to start? Book Riot’s A Beginner’s Guide to Manga has you covered. If you’re already a manga aficionado, 10 Manga to Read After Catching Up With One Piece has some great suggestions.