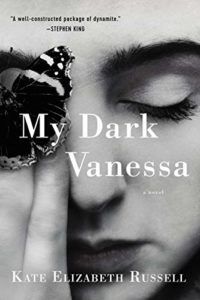

It’s fitting that Kate Elizabeth Russell’s novel My Dark Vanessa was released on March 10, the day before Harvey Weinstein was sentenced to 23 years in prison. A Weinstein juror was almost disqualified for reading an advance copy of this novel. The book is hard to read in places because the abuse is so graphic. It’s also the antithesis of the idealized teacher/student “romances” that I criticized in 2018. Without using the exact term, it’s the clearest fictional depiction of trauma bonding I’ve ever read. Here, I defined a trauma bond as “an unhealthy but intense connection to a dangerous person.” Criticisms that the protagonist, Vanessa, reacts unrealistically are unfair because all survivors process trauma differently. Vanessa was obviously horribly abused, but it’s actually common to defend or keep in touch with with an abuser. Even as an adult, decades later, Vanessa refers to her abuser only as “Strane.” She’s stuck in a liminal space, always unable to think of him as her teacher (Mr. Strane) or as her equal (Jacob). She also rejects words like victim, abuse, rape, or survivor. Most of Vanessa’s teachers at Browick, a fictional boarding school in Maine in 2000, have poor boundaries. In fact, the few teachers with healthy boundaries seem cold and standoffish by comparison. They all eventually end up enabling and hiding Jacob Strane, a prolific abuser. It’s a cultural, systemic problem at the school. Vanessa first meets Strane when she’s his 15-year-old student in English class. He targets her almost immediately. To adult readers like me, Strane seems slimy, insincere, and predatory from the beginning. That’s the point, though: Vanessa is young and insecure enough to bask in his attention. Their complex trauma bond lasts for the rest of his life and severely impacts hers. She constantly idealizes and rationalizes the abuse. Even when she knows she isn’t to blame, she’s in denial: “It wasn’t rape rape.” Vanessa’s frenemy, Jenny, calls Strane a “creep” and a “misogynist.” Vanessa accuses Jenny of “jealousy” of their “special connection,” but clearly Jenny is right. Without the trauma bond, other kids see him for what he is. Much of the book is hard to read. As Roxane Gay pointed out in her Goodreads review, there are many scenes of child sexual abuse. I know that survivors often have intrusive memories, but there’s no need for the book to devote so much explicit detail to graphic descriptions of Strane’s body and his abuse. Vanessa’s traumatic memories are unreliable. She dissociates, or imagines leaving her body, during rape. She even conflates details of Strane’s abuse with Lolita, one of his favorite books. This doesn’t mean that Vanessa’s lying; rather that traumatic memories can be complicated. When Vanessa stays overnight at Strane’s house for the first time, she’s still his underage student. She steals an unused black negligee from her mom, hoping she’ll look adult. However, Strane has already bought her pajamas with a childish strawberry print. Details like this make my skin crawl. Vanessa thinks Strane is making her into a woman with a fascinating story. Ironically, it’s exactly the opposite. As a pedophile, he wants her because she’s literally a child. Eventually, he’s no longer attracted to her, but still keeps her emotionally entangled. Strane’s manipulation extends far beyond Vanessa to the entire school, including parents. Like many real abusers, he seeks pity and makes “predictions” that are actually veiled threats. Strane tells Vanessa that if she reports him, the consequences could be equally serious for both of them. That doesn’t sound right to her, but she wants to trust him. He says that she could be expelled or even put in foster care. Eventually, she is expelled from Browick for her “false accusation.” Jenny figures out that Strane actually orchestrated everything. This is all well plotted and explained. Strane manipulates Vanessa into considering rape a romantic, loving relationship. She’s internalized his lies and idealized him. Strane keeps this trauma bond so he can control her, hoping she’ll never report him. Yet he turns it on her, saying she’s the one with power over him! This novel shows why survivors often deceive themselves or protect their abusers. Vanessa realizes that Strane’s treatment of her fits the definitions of abuse and grooming, but still romanticizes it: “To be groomed is to be loved and handled like a precious, delicate thing.” This is one of many moments when readers can see through Vanessa’s unreliable, first-person narrative. She insists that Strane was “careful” with her, but his actions were obviously illegal, abusive, and brutal. When Vanessa confides to her young college professor, Henry Plough, that Strane raped her, she calls that a “lie.” Ironically, it’s actually the first time she’s ever told the truth about him. Vanessa’s friendship with Henry is interesting. It’s not sexual but intimate—maybe borderline emotionally inappropriate. Abuse survivors sometimes seek out relationships that repeat old patterns, even when these new relationships aren’t abusive. Henry’s much younger wife is his former college student. I don’t think that the novel is necessarily drawing a comparison between Strane and Henry. Instead, its close focus on Vanessa’s development shows why she keeps seeking out people with poor boundaries in an attempt to cope with the abuse.

Read More:

2020 Debut Fiction Novels My Problem With Lolita