Women’s heroes are everyone’s heroes! In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote, we read books that are by, for, and about powerful women of all ages. A pre-teen who helped discover the world’s first dinosaur bone, a young women in the early 20th century who braved the illness and death of the radium factories and fought a groundbreaking battle for workers’ rights, or teens—one black, one white—who rely on each other to survive a night of violent race riots in their city—these are the stories of remarkable women of history and resourceful everyday girls. Pockets are mentioned about 70 times in Alix E. Harrow’s forthcoming novel The Once and Future Witches (Orbit, October 13, 2020), a book that can best be described, in Harrow’s words, as “suffragettes, but witches.” (My Kindle ARC says it’s 72 mentions; I consulted with Harrow for confirmation, and her Word doc says 69.) From the novel (page 51 in my copy): “It’s one of those respectable, pocketless affairs that obliges ladies to carry stupid little handbags, so Juniper can’t carry so much as a melted candle-stub or a single snake tooth with her. Bella informs her that this is the precise reason why women’s dresses no longer have pockets, to show they bear no witch-ways or ill intentions, and Juniper responds that she has both, thank you very damn much.” It is 2020. Women—at least white women like me—have had the right to vote in the USA for 100 years. But we still lack pockets in our garments in any meaningful fashion. Allow me to elaborate with an anecdote. In 2016, when my son was 10 years old, I washed jeans belonging to him, myself, and my husband, and noted the difference in pocket size. I was able to fit my entire hand into my 10-year-old’s pocket. In my husband’s jeans, my hand went in up to the elbow. In mine? My fingers went in all the way to…the second knuckle. All three pairs of jeans were commercially made and widely available. Does this story mean that all pockets are unequal? No…but they are.

A Very, Very Brief History of Women’s Pockets

(Note: this history covers American pockets and some British pockets but largely ignores Indigenous populations and the rest of the world.) Historically, women’s clothing has been pocketless for…basically ever. At one time, all clothing was pocketless and people of all genders carried their sundry goods in bags. But while men’s garments have had pockets sewn in since sometime in the 17th century, women have at various times used pockets that tied around our waists with strings, carried an assortment of bags, and generally suffered while our male counterparts stuffed their pockets full of whatever they wished to carry and stuck anything too large in our bags.

Pre–17th Century: everyone carries bags if they carry anything17th–19th Centuries: menswear gets pockets; women’s pockets are little pouches on a string that can be tied around their waist and worn between petticoat layersEarly 19th Century: fashions change and women’s clothing lines are too slim for pockets; reticules (handbags) come into fashionMid 19th Century: sewing pockets directly into seams comes into fashion—but does the trouble end there?

I feel quite certain that the history of pockets in the 20th century is worthy of a whole dissertation, but I am not including it here as I am focusing on the suffragist movement of the second half of the 19th century and first fifth of the 20th century.

Further Reading on the History of Pockets

Mansfield University Press’s The Culture of Fashion: A New History of Fashionable Dress by Christopher Brewer covers 600 years of fashion, focusing on Europe and AmericaIn Taschen’s Fashion History from the 18th to the 20th Century (Bibliotheca Universalis) the Kyoto Costume Institute examines world women’s fashion from the 18th century to the present PhD candidate Karen J. Kriebl’s From Bloomers to Flappers: The American Women’s Dress Reform Movement, 1840–1920 can be found here.The Politics of Pockets by Chelsea G. Summers covers much of the history of pockets, from the starting point of Hillary Clinton’s suffrage reminiscent pant suit at the 2016 DNCA follow-up from Summers: When it comes to women’s pockets, size really does matterThe Gender Politics of Pockets by Tanya Basu focuses mainly on modern pocketsThe Bewildering and Sexist History of Women’s Pockets by Chanju Mwanza gives a brief but good overviewAnd for a British perspective, The V&A gives us A history of pockets

But what, you may be wondering, has this to do with suffrage? I AM SO GLAD YOU ASKED. I hope you’re sitting down, this may be a lot.

Bicycles and Hatpins and Knitting Needles, Oh My!

The modern bicycle* was invented in 1885 (earlier variations on the idea had been around since 1817) and by the mid-1890s it was a popular form of transportation for people of all genders. In 1895 The New York Times published an article on women’s bicycle costumes (unfortunately, only the abstract is available to non-subscribers). In the article, a (male) tailor was quoted extensively, claiming that all women wanted bicycle costumes with pockets specially made to hold their pistols. As you might assume, men hated this, because why would a woman need to carry a pistol except to shoot men? I assume this is largely accurate, as men are the number one threat to women’s lives. (Please note that intimate partner violence happens in relationships with people of all genders.) *There is a whole nother article in me on the freedom the bicycle allowed women, but The Atlantic has already covered it more than adequately, with extensive notes about bicycle costumes and how much men hated them. Is there any truth to the claim that women were en masse electing to carry pistols in their pockets? I have absolutely no idea. I kind of doubt it, while hoping it is 100% true. Around 1903, women—still largely lacking pockets—began to use their hat pins as weapons against “mashers,” lecherous men who took advantage of crowded public transportation and anonymous street encounters to grope women. You have likely never seen a hat pin; imagine a straight pin, as used for sewing, but the approximate size of a bread knife. Hat pins went through a hat and secured it to the wearer’s hair beneath (which was often itself pinned up). They were no small item, and likely hurt like the dickens to be stabbed with. This was so effective that men in Chicago and other cities would go on to vote for laws against the hat pin peril, further proving that women needed the vote. L. Frank Baum satirized this so-called hat pin peril in the second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz, with General Jinjur and her army using knitting needles as weapons in their revolt against the Scarecrow’s rule. Baum’s satire does not appear to be in support of suffrage, though he himself supported it; the book does end with Jinjur and company taking the household duties back over from their ridiculous husbands who cannot handle them, which is hardly progressive.

Queering the Suffrage Movement

Queer women of the suffrage movement (many of whom might today be trans men or nonbinary, but at the time that language was nonexistent and the concept largely unknown) such as Annie Tinker and Margaret “Mike” Chung*, often wore men’s clothing with its ample pockets. While this choice is more likely tied to their gender expression than specifically to pockets, Tinker in New York and Chung in San Francisco certainly made waves in the 1910s—and were largely denounced by the mainstream suffrage movement because they were not making themselves appealing to men in order to win the vote. A few years later, San Francisco lawyer and president of the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs Gail Laughlin notably refused to wear an evening gown (her day wear was menswear) until pockets were added. *Learn more about Mike Chung, who was the first known female Chinese American doctor, in Doctor Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards: The Life of a Wartime Celebrity by Judy Tzu-Chun Wu. Suffragist suits were briefly popular as well, bearing some resemblance to our modern day women’s suits with the important addition of as many pockets as could be added. Based on both menswear and bicycle costumes, suffragist suits were popular only briefly but certainly managed to annoy and amuse during their time in the spotlight.

Satire and the Suffrage Movement

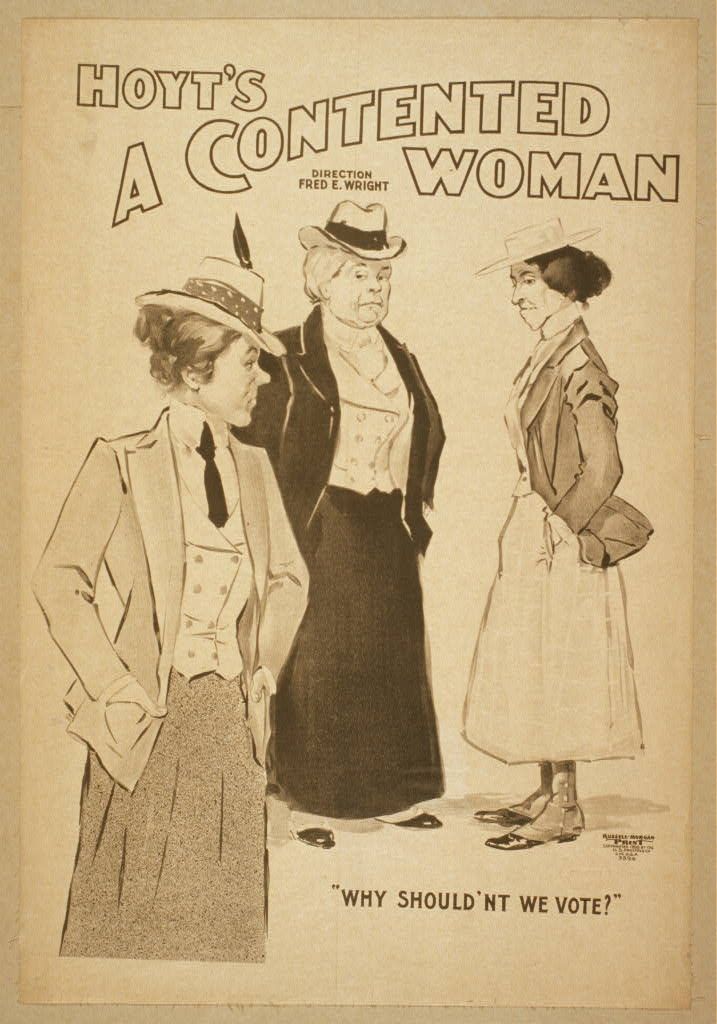

Charles Hoyt was a playwright who met his second wife, Caroline Miskel, when she starred in his satirical play A Temperance Town. He went on to write A Contented Woman for her to star in: another satire, this one showing the divide between miserable suffragists and happy housewives. I cannot find any information on whether Hoyt was personally pro- or anti-suffrage; he died in 1900. The play’s poster shows discontented suffragists, hands in their pockets. From 1914 to 1917, Alice Duer Miller published a column in the New York Tribune called Are Women People?, later collected into a book of the same name. I close with her 1915 poem from that column.

“Why We Oppose Pockets for Women”

(Miller’s work is in the public domain, and the entire book is available at Project Gutenberg.) After the vote was won, bicycle costumes and suffragist suits were largely abandoned. We won the vote but lost the battle for pockets. A note: most of the authors mentioned in this article are white. American suffrage was won at the loss of true equality, as the white women leading the fight decided that racism would prevent them from winning if they had Black women in leadership; In fact, several prominent suffragists fought against the 15th amendment, arguing that Black men should not have the vote before white women. The story of American suffrage is complex and full of white supremacy, and the 19th amendment was truly only for white women.