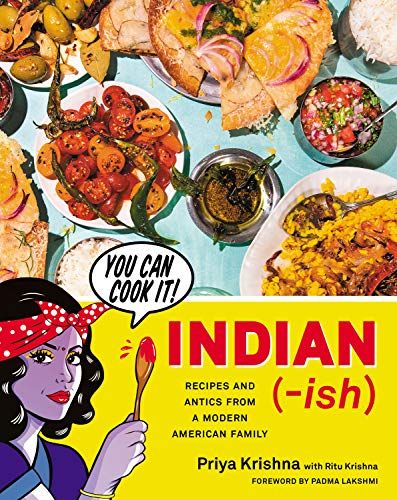

So yes, I’m a foodie. And yes, I’m that girl at the restaurant posting food pics on Instagram. And yes, I will stand up to get the perfect angle. Eat your heart out. It made perfect sense that I would marry my two loves by reading cookbooks. Pretty pictures of food. Recipes that I’ll just use as suggestions. And of course, the stories. The late Anthony Bourdain was onto something when he helped audiences realize that food is the perfect vehicle to talk about oneself and one’s culture. We are what we eat. Of course, my bibliophile brain prefers to read stories as opposed to recipes, which, let’s be honest, are glorified chemistry experiments (but delicious). As such, I found myself drawn to how the food was incorporated into the life of the cook. Last year, I ended up reading close to 300 books because, well, the world was under lockdown, and I desperately needed an escape. I decided to diversify my cooking skills and purchased several cookbooks by chefs and personalities I admired, determined to learn something new in the kitchen. My intentions were pure: I wanted to learn new cooking techniques. But the reader in me couldn’t read through the recipes. Instead, I found myself attracted to the introductions, the blurbs that always come before a recipe, and even the acknowledgements. Cookbooks are fascinating to me as a reader because they are essentially technical manuals filled with the aforementioned glorified chemistry experiments. But while reading many of them during the pandemic, I realized that cookbooks are more than cups, tablespoons, and the good vanilla. When done properly, they serve as cultural markers. The cooler cousins of textbooks, if you will. You see cooks all the time now using their cookbooks as vehicles for their stories and even using the recipes as exhibits for the museum of their lives. A lentil stew isn’t just a nourishing winter dish but also what the cook made for their children when they got sick. A pasta dish isn’t just a fancy dinner staple but what the cook’s grandma used to make in the old country. Every recipe has a story. And what makes cookbooks so cool is the fact that after publication, they truly belong to their readers, who in turn will make their own stories with the recipes in a tangible way. One of my favorite food writers, Priya Krishna, published Indian-ish with her mother in 2019. I first heard of the cookbook whilst reading her article “How Pizza Became An Unlikely Symbol Of My Indian-American Identity” on Refinery29. While I was making of list of cookbooks to purchase last year, I remembered the article and decided to purchase a copy of Indian-ish, and I was taken with how food was the medium she used to tell her family’s story, which was both Indian and American. Roti pizza. Saag Feta. Shrimp Pulao with Quinoa. Recipes that reminded her mother of home but that had adapted ingredients readily available at the supermarket. Curious, I purchased other cookbooks by famous chefs and food writers. The next one that caught my attention was Jerusalem by Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi. Ottolenghi grew up in a Jewish family in Ramat Denya, Jerusalem, while Tamimi grew up in in a Muslim family in the Old City of East Jerusalem. Together, their stories and food painted a complex and beautiful picture of a complex and beautiful place: Jerusalem. I’ve done a lot of reading and personal research into the city but never considered that a cookbook would add a new and important layer to my understanding of modern Jerusalem. I’m certainly not naïve enough to assume that eating the same foods will make everything better, but after reading so many articles in The New York Times and listening to so many podcast episodes on NPR and watching yet another special on CNN, it was just refreshing to see something as personal and individualistic as a plate of food in a place that is too often defined by others rather than its residents. As someone who has read her fair share of books, I think I’ve become pretty good at sussing out the good stories from the bad. I’ve also learned that not all great stories need to be literary fiction and subsequently reviewed by The New York Times Book Review or awarded The Man Booker Prize (don’t mind James Beard). A great story just needs to connect with its readers. It turns out that a recipe for pumpkin bread is sometimes all it takes.